In preparation for Hebrew Book Week, we visited the home library of ancient book conservator Reuven Campagnano

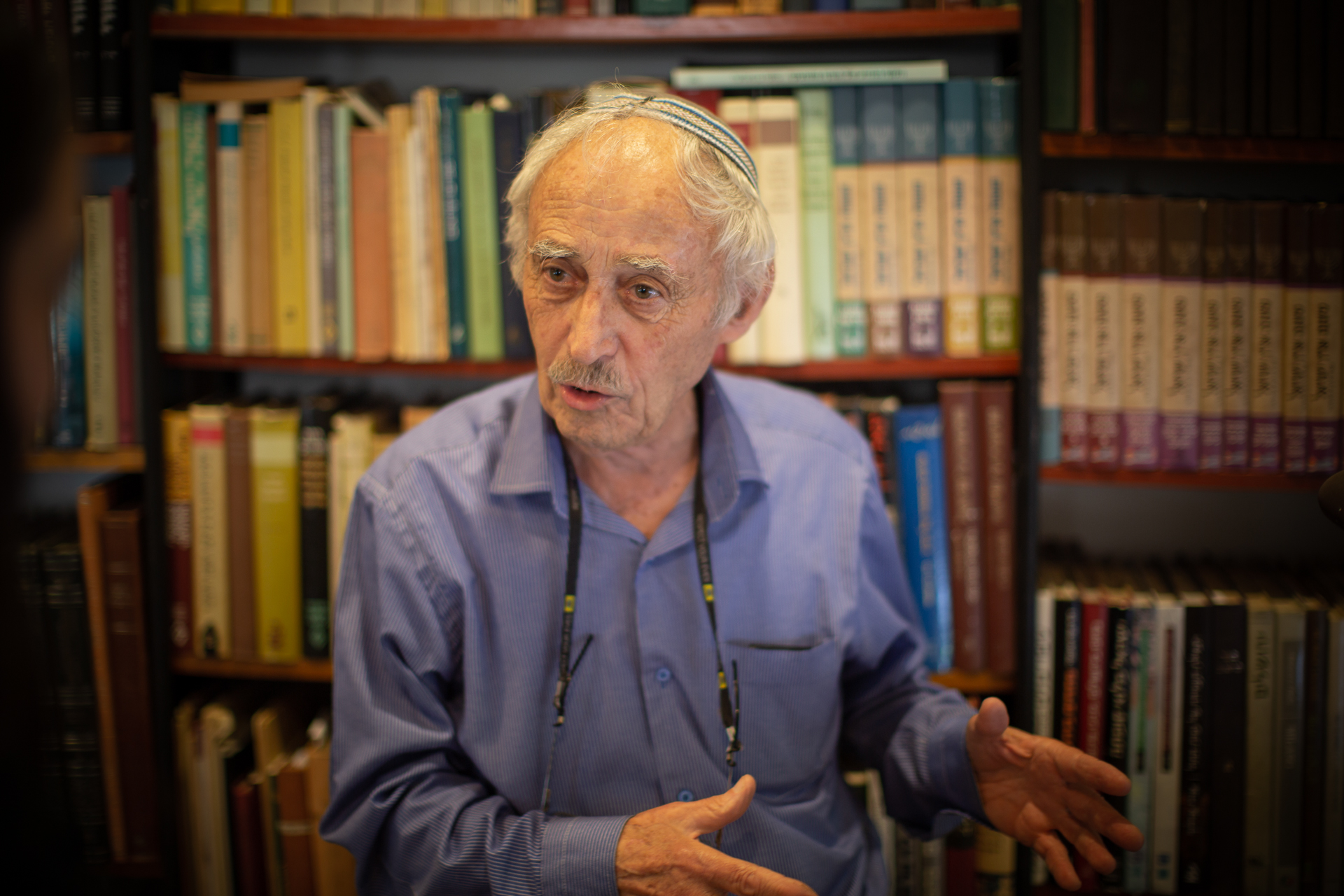

Hana and Reuven Campagnano (photos in the article by Nikolai Busygin)

Reuven Campagnano (born in 1942) immigrated to Israel, to the kibbutz Kvutzat Yavne, at the age of three with his mother, brother, and cousins in March 1945, after the liberation of Florence. He spent the war years with an Italian couple who hid him; he maintained contact with them for many years after the war. He was an intelligence officer in the army until the age of 40 when he was demobilized with the rank of lieutenant colonel. From his mother Reuven inherited the talent of working with his hands, and from his father – the love of books, and in combining these two passions he found himself a second career – restoring and binding ancient manuscripts.

Campagnano's library holds books on Judaism, history and Zionism, many versions of the Jerusalem Talmud and entire series of classical Hebrew literature, including books by Uri Zvi Grinberg, Shmuel Yosef Agnon, Sholem Aleichem, and others. When I ask him if he has read most of the books in his collections, he answers: “Of course!”. And the reason behind his own huge book collection is, “Because I'm learning all the time.”

Tell us about the books that have been on an interesting journey before ending up on your shelves.

Campagnano opens the door of the bookcase in the living room and reveals a decorated Torah scroll. He says: “I brought this Torah scroll from the community of Alessandria in northern Italy. My grandfather was a rabbi there until the day he died, at a rather young age. My father was murdered in Auschwitz after being captured in Florence. I immigrated to Israel as a child after the war, and when I grew up, I returned to the community in Alessandria and told them that I wanted two Torah scrolls: one in memory of my grandfather and one in memory of my father. I received one, and I have it here. The covering for this Torah was sewn by my mother. Two weeks ago, my grandson read from this scroll at his bar mitzvah ceremony, exactly one hundred years after my father’s bar mitzvah; he probably read from it too.”

As a bookbinder, Campagnano has worked on many ancient manuscripts and special books. One of them is the magnificent facsimile edition of the Aleppo Codex, a Hebrew manuscript of the Bible that is considered to be particularly accurate and important: “Magnes Press asked me to bind 50 facsimile copies of the Aleppo Codex, and I told them that I would not bind 50 but 51 so that at the end the job I got to keep one copy for myself. The Aleppo Codex was held for years in the Jewish community of the Syrian city of Aleppo, or Halab. During the Second World War, the community agreed that a Jerusalem scholar would come to see the book, and the university sent my grandfather on my mother’s side, Umberto (Moshe David) Cassuto, who was a Bible professor. Books were later written based on his diaries from that visit and the research that followed.”

Finally, he reaches towards his collection of Haggadahs and pulls out the Haggadah with Abarbanel's commentary. He inherited this copy from his grandfather's library. At the end of the manuscript there appears the signature of the Italian censor (who was a converted Jew): “Checked by Brother Luigi of Bologna, 1599”. The censor checked the copy and deleted anything that the church considered to be inappropriate and against Christianity. There are sentences crossed out in ancient ink.”

What is the book you have reread the most?

“The Tanakh. It couldn’t be any other way. I've been reading it since the age of five: when we were living in a big wooden box in Kvutzat Yavne, we tried to warm up from an oil burner, and I would lie on the carpet and read the Bible. It interested me. And out of the whole Tanakh, I especially like the historical books.”

Which book from your library would you recommend to a friend?

“I would recommend my own books (a series of seven books that make the Jerusalem Talmud accessible), because people are afraid of the Jerusalem Talmud. There is a very strong reluctance to approach the Jerusalem Talmud, especially among yeshiva students, who trust the Babylonian version. When I see a person of a scholarly appearance, I usually ask him if he opens the Jerusalem Talmud when he sees a reference to it in the Tosafot to see the source, and the answer is ‘no’. When the Babylonian Talmud references Tanakh or another source, he does check against it.

What drew me specifically to the Jerusalem Talmud is that it is neglected – a whole branch of ancient literature that was abandoned because of the Geonim who pushed the Babylonian one. This is also the reason that fewer copies of the Jerusalem Talmud survived and that it was commented on less. My books are meant to remove this barrier.”

How do you decide which book to purchase and keep?

“I don’t buy books that are read and passed on. I receive them. I read a lot of fiction, but I don't buy it. It's a waste of money. I only buy non-fiction and classic Hebrew literature.”

Do you lend books?

“I do lend books. I used to have a notebook with the list of the books that I lent, but I neglected it. I trust people to bring the books back.

”

What tip would you give to beginner hoarders?

To this question, Reuven’s wife Hana replies: “We don’t take out the books one by one to clean them; we use the books, and that’s what keeps them clean. And another piece of advice for young people: take everything, and filter later on.”

This article was originally published in Hebrew.

Check out Beit Avi Chai’s Hebrew Book Week Festival (events in Hebrew plus Story Time for kids in English).

Also at Beit Avi Chai