What would a psychological analysis of these characters look like? What are the psychological motivations behind their actions? And how did they themselves experience the events described in the Book of Esther?

Imagine a palace like a bustling anthill. Its wings are teeming: the banquet hall, the harem, the main gate. Now imagine the characters within it, also bustling. And like flesh and blood humans, the characters scheme, hide, are anxious, plot, get drunk, fall into depths of depression and emerge from it, mourning and rejoicing.

This is what Ahasuerus’ palace looks like in “Ahasuerus’ Megillah”, a book of commentary on the Book of Esther and the holiday of Purim by Dr. Azgad Gold (published in Hebrew by Resling). In its first part, the book analyzes the motivations behind the actions of Ahasuerus, Haman, Esther, and Mordechai. Its second part is “dedicated to theological aspects arising from the interpretation” in the first part; in it Gold raises faith-based questions that combine poetry with the caution of a scientific and medical professional.

Gold is the director of the Forensic Psychiatry Unit at the Be’er Ya’akov Mental Health Center, a privately practicing psychiatrist and psychotherapist, and a doctor of medicine and philosophy. “Megillat Esther doesn’t reveal much,” he admits when asked how he added depth to its characters. “In our consciousness, Mordechai is a prominent figure, but when examining the text, we discover he is less so. In fact, the text focuses significantly more on Haman and Ahasuerus. Haman is a narcissist, and the Megillah exposes his thoughts more than any other character – as befits a narcissistic figure. In contrast, Ahasuerus is revealed as having a paranoid personality. The paranoiac is ‘hidden’ because, as a paranoiac, he works to conceal.”

And Esther?

“The Megillah is more generous in describing male characters. They have more textual anchoring points that can serve as a basis for interpretation and imagination. Nevertheless, in Esther’s case, I could imagine her psychological state. She undergoes a transformation from complete passivity to complete activity. Her passive state is typical of people with melancholic or depressive traits. The beauty of her transformation lies in the fact that nothing changes in her external environment. The change occurs in her soul. She manages to disconnect from her past and the circumstances of her arrival at the palace, where she was brought entirely passively, while being required to hide her identity. Esther learns to forgive herself, turn the page, and understand that she is the source of her own redemption.”

What’s new about the reading of the Megillah that you propose in the book?

“At the basis of the Megillah is a story, and the story is about kings, queens, ministers. It’s a story about royal decrees that are able to change destinies. The unique question I ask is: What of all this is derived from a human state of mind? From personal tendencies? Because even if you look at ‘Trump’s Megillah,’ you’ll discover personal patterns.

“The personal imprint demands that we look at it, and I look at it differently from psychologists and historians. Psychologists analyze the individual but don’t look at the world around them. In contrast, historians do not examine the inner life of the individual. I offer an additional link connecting personal processes to historical processes. The Book of Esther is an archetype of this concept, the meeting point of psychology, history, and literature.”

Like a Detective Novel

In his book “The Shammais” (published in Hebrew by Yedioth Books), Gold examined the motivations of the House of Shammai. “I love working with halakhic texts,” he says. “For this reason, I was also drawn to the story of the Megillah. It has living characters – it’s easy to enter their world and imagine them. I wanted to examine how the characters themselves ‘experienced’ the course of events. As a reader, we perceive the Megillah as a single unit. Did the characters experience it the same way?”

In “Ahasuerus’ Megillah,” Haman’s megalomaniacal motivations merge with Ahasuerus’ paranoid tendencies. The fates and plans of Mordechai and Esther undergo metamorphoses and reversals. The book is rich in developments, some of which are thrilling. In its second part, all these fluctuations converge into a theological argument that even secular readers will enjoy.

The book reads like a thriller at times. It seems you, the author, are present in the book like a detective.

“I’m attracted to the detective thriller genre because it echoes my world as a forensic psychiatrist. In my role, there’s a convergence between the world of the psyche and the world of law. The questions asked are related to dead and living people: by virtue of my role, I must determine if a person with dementia can write a will, if a person is fit to stand trial, if a person had control over their actions when committing a crime. I must ask myself what was going through their mind when they committed the offense.”

Can you describe the moment when the Megillah characters rise from the text and become three-dimensional?

“It’s hard for me to answer this precisely. Everything starts with words. I first focus all my attention on a meticulous examination of texts referring to each character. Sometimes I try to read the text not necessarily chronologically, but concentrate on various descriptions of each character to try to decipher them. I tend to read stories through the people that make them up. In doing so, I try to pay attention to the described content, the style in which the content is described, and think about literary alternatives that could theoretically express the same content, and from there try to understand what the text represents or expresses.

“Word after word, description after description – these create a certain pattern in my imagination that suddenly comes to life and is born as a tangible and very accessible portrait. Like a character in a movie, if you will. This process, partly related to subconscious processes, is likely influenced by professional knowledge and experience, and also by personal experience and intuitions.”

Is this similar to the moment when you examine legal documents? When you need to breathe life into the moment a person committed a crime?

“A certain parallel can be drawn between the process of personality analysis in a literary text and analyzing medical records when trying to determine a mental state in a psychiatric opinion. It’s an attempt to understand the situation and its human aspect: What were the basic assumptions about reality for Mordechai or Ahasuerus, for Haman or for a person who committed an offense? What were their motivations? Did these intentions materialize?

“However, there are also significant differences between people who committed criminal offenses and the Megillah characters. In analyzing a literary text, the character is not accessible to me beyond that text. On the other hand, in most cases of writing a psychiatric opinion – for example, regarding criminal responsibility – there’s a component of direct examination of the subject, although there are also situations where the only way to decode the mental state of the subject is truly textual alone, such as questions of competence to perform financial actions like writing a will.

“Another difference is related to the fact that the target I aim for when analyzing a literary character is broad. The aspiration is to sketch the character’s personality structure as richly as possible, in all its aspects. In contrast, a psychiatric opinion is usually limited to examining a mental state in a very specific context, around a specific event or action. For example, whether at the moment of committing the offense, the subject understood the nature of their actions and their inherent wrongness.”

In All Our Lives, There’s a Shipwrecked Boat with Treasure

The second part of “Ahasuerus’ Megillah” captures the characters’ motivations and actions to build a theological argument. Gold writes beautifully about the motif of “double concealment” in the Megillah. Unlike hide-and-seek, where we know something is hidden and must search for it, in the Book of Esther, there seems to be no divine hand, at least according to Gold, an observant Jew.

“The concealment of God and religious motifs in the Book of Esther is so deep that it seems there’s no concealment at all,” he writes. “The entire plot, from beginning to end, can be understood against the backdrop of the human factor. The concealment is not experienced intuitively, and therefore, what is concealed is not truly required to conceal reality.” Later, he writes: “The Megillah, written and formulated as God’s concealment from the world and human soul, becomes a legitimate perspective within religion. This is a challenge that a person can internalize without removing themselves from the religious framework.”

This seems like an address to religious people undergoing a crisis of faith. How relevant is your book to secular or non-Jewish readers?

“One of the most enthusiastic reviews I received came from a skeptical secular person who usually scorns ideology. The Book of Esther is precisely the text that secular and non-Jewish people can connect with. The discovery of double concealment eliminates all intermediaries. I’m not sketching God in the book. I’m talking about a shipwrecked boat we don’t know exists, and a treasure within it we don’t know exists. What’s important is the partnership of seekers. Escaping the narcissistic state is what matters. Esther’s courage, her resourcefulness – this is, in my view, a revelation of the holy spirit.”

Is this the holy spirit of a Buddhist too?

“That’s an interesting question. Ultimately, the question is whether a person remains within themselves or connects to something larger. In all our lives, there’s a shipwrecked boat with a treasure, and the question is when we become aware of its existence. I call this the holy spirit pulsating within us, and it won’t pulse if there’s no opening of this window, which the double concealment hides.”

Join Beit Avi Chai’s special Thursday-evening Kabbalat Shabbat in honor of Purim, on March 6.

This article was originally published in Hebrew.

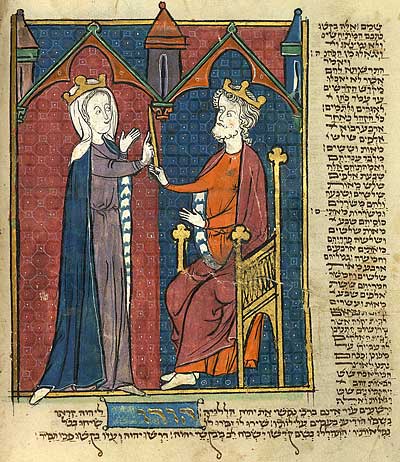

Main Photo: Esther reveals Haman's plot to Ahasuerus. Painting made by Jan Victors\ Wikipedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai