Every Hebrew word is a time capsule. Etymologist Elon Gilad reveals how borrowed terms and linguistic innovations transformed an ancient liturgical language into modern Israel’s living, evolving tongue

The resurrection of Hebrew is one of the most remarkable stories in the history of languages. But the Hebrew we speak today isn’t just an ancient language dusted off and put back into service. As journalist, etymologist, and historian of Hebrew Elon Gilad explains, every word is a “time capsule,” and understanding where our words come from offers an unexpected path into the grand narrative of human history.

Gilad’s journey into Hebrew etymology, though, began more ordinarily: by moving apartments. “I moved to a tiny apartment on Luntz Street in Tel Aviv,” he recalls. “I’m a nerdy type who’s interested in street names.” What he discovered about Abraham Luntz – a blind scholar who coined hatzil, the Hebrew word for eggplant – sparked a transformation from a night editor at Haaretz into one of Israel’s leading enthusiasts of Hebrew etymology. Since January 2013, he has published a weekly column in Haaretz exploring the hidden histories buried in everyday Hebrew words, amassing 128,000 Instagram followers and reaching audiences as far afield as Indonesia, South Africa, and the Czech Republic.

His work also serves a deeper purpose. “I try to give non-religious Jews a way to connect to their Judaism,” Gilad explains. “Because of the politics in Israel, a lot of my friends, who are secular Jews, have a dislike of anything that smells Jewish. I think that’s really sad – we shouldn’t sever the branch that we grew on.”

Who said that hasida means stork?

What, then, does Hebrew etymology tell us about Jewish history? Consider the word hasida, the modern Hebrew word for stork. It appears in Biblical lists of non-kosher birds, but for most of Jewish history, nobody was quite sure which bird it actually referred to. “The tricky part about words in the Bible is that we often don’t know what they actually mean because nobody speaks biblical Hebrew anymore,” Gilad says. Ancient Greek translations varied, and the Latin Vulgate also offered multiple possibilities, but none of them were stork. The Aramaic translation, meanwhile, simply called it a “white bird.” Saadia Gaon, the great tenth-century Jewish scholar, used the Arabic word saqar – a general term for hunting birds like falcons. Spanish Jews followed this interpretation.

Then came Rashi and his canonical commentary on the Bible. Rashi was the first to identify hasida as the stork. “One rabbi was scandalized because his congregants were eating storks although he knew they weren’t kosher,” Gilad recounts. “Another rabbi said it was fine because of their ancient tradition.” Eventually, though, Jews stopped eating storks all together, all thanks to Rashi’s educated guess.

Civilizational layer cakes

Hebrew vocabulary functions like an archaeological tell – civilizational layer cakes where each stratum reveals a different historical period. “You can see the loanwords change as the years pass, reflecting the historical circumstances,” Gilad explains. In the Bible, we find Egyptian, Akkadian, and even Hittite words. Late Biblical and rabbinic Hebrew absorbed Persian and Greek terms when those empires dominated. Following the rise of Islam, Arabic words flooded into Hebrew, particularly in mathematics, philosophy, and science. Finally, modern Hebrew draws from Yiddish, Russian, French, and English – first from the British Mandate period, and later from the United States. Meanwhile, Hebrew slang in the 1960s through 1980s drew heavily on Arabic, reflecting the aliyot from Middle Eastern and North African countries.

Some borrowed words hide their foreign origins so well that native speakers never suspect them. Dat, the Hebrew word for religion, comes from ancient Persian, where it meant law. Nimus, meaning politeness, derives from the Greek nomos, also meaning law. And then there’s artic – the Hebrew word for popsicle – which has perhaps the most surprising etymology of all.

“In the beginning it meant “terrifying” in proto-Indo-European,” Gilad explains. “Harticos. They were terrified of bears.” That word evolved into Greek articos, meaning bear. Because the Great Bear constellation (the Big Dipper) always appears in the northern sky, the word came to denote northern regions – hence Arctic. In the twentieth century, Belgian Jewish businessmen investing in Israel chose to name their popsicle company Arctic, but Israelis found it difficult to pronounce, so they simplified it to artic. Thus, a word born from the fear of prehistoric bears now means a frozen treat in the Israeli heat.

The father of Hebrew linguistic innovations

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda is rightly celebrated as the father of linguistic innovations such as the one above, but the reality of Hebrew’s revival is more complex and collaborative than popular mythology suggests. “He was the driving force, but he wasn’t alone,” Gilad clarifies. Ben-Yehuda gathered a small group of believers together, including Luntz, Rabbi Yehiel Pines (who coined the word agvaniyah for tomato, based on the Hebrew root for the word ‘lust,’ reflecting a European notion that tomatoes were aphrodisiacs), and young teachers scattered across Jewish towns. But by the start of the twentieth century, after twenty years of Ben-Yehuda’s tireless work, the project looked like a failure, as only a tiny group of people spoke Hebrew in daily life.

The breakthrough came with the Second Aliyah and the British Mandate, when large numbers of ideologically motivated Jews arrived in Palestine. “Ben-Yehuda was very old by then and wasn’t the leader of the process,” Gilad notes, “but he had already coined many new words and raised his children to speak Hebrew.”

Ben-Yehuda coined some 80 words still in use today – the poet Haim Nahman Bialik comes in second place with only half as many. The revival of Hebrew was ultimately a collective enterprise, driven by ideology, necessity, and the contributions of poets, teachers, and ordinary people.

Hebrew continues to evolve

Even today, Hebrew continues to evolve in ways that reveal how languages change. One particularly fascinating shift involves binyan hifil, one of Hebrew’s verb categories, which begins with the sound hi. “Starting in the 1970s, young people started saying hefil instead of hifil,” Gilad recounts. “I was born in the early 1980s so I started saying hefil despite knowing it’s incorrect.”

By the 1990s and 2000s, educators noticed the shift and tried to fix it, but their efforts were futile. “Everyone born after 1974 was pronouncing it wrong,” Gilad notes. “There’s no good explanation as to why it happened.” Now it’s no longer really considered a mistake – it’s simply how Hebrew is spoken by most Israelis. “That’s usually how languages change – the younger generation starts speaking differently.”

Making Jewish history relevant to modern Israelis

For Gilad, teaching about etymology is a way of making Jewish history relevant to modern Israelis. “You could theoretically study Jewish history without dealing with Hebrew etymology at all,” he admits. “By studying it through the lens of etymology, I achieve several things. First, I make it relevant to modern Israelis.” They might have no interest in who Saadia Gaon was, but they might be curious as to why the word for stork is hasida. “By using something that actually has an impact on their life to explore ancient Jewish history, I can get them interested in topics they would otherwise not be interested in,” Gilad explains. “There’s a pay-off. It’s a trick to fool people into being interested in our ancient history.”

This approach also highlights overlooked figures in Jewish history. Gilad points to Assaf HaRofeh (Assaf the Jew), a physician from the late Byzantine/early Arab period who wrote the earliest surviving Hebrew medical textbook. He played a crucial role in coining the term rakefet, the Hebrew word for cyclamen. “It allows us to get a more granular view of Jewish history that we would otherwise skip over,” Gilad observes.

Hebrew’s story is unique – a language that survived for two millennia as primarily a written and liturgical tongue before returning to everyday speech. Each borrowed word, each coined term, each shifted pronunciation tells a story about who Jews encountered, what they learned, and how it changed them. “And I think stories of words are fun,” Gilad concludes, “whether in Hebrew, English, or other languages.” So every time we say hatzil or agvaniyah or artic, we’re speaking not just a language but a history, continuing a conversation that has lasted for thousands of years.

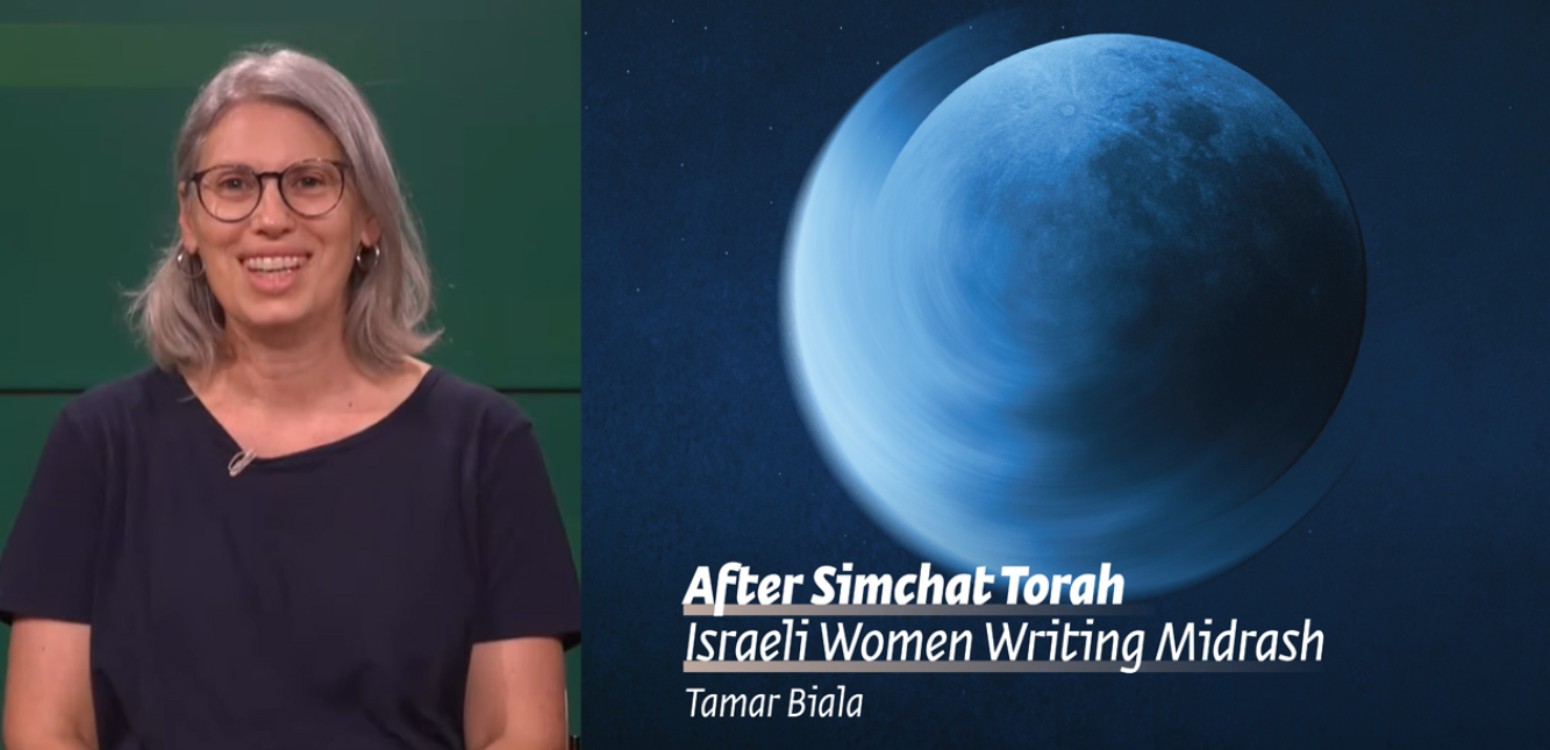

Also at Beit Avi Chai