Free choice is a cornerstone of moral responsibility—without it, concepts like judgment, blame, and punishment become meaningless. Yet, the notion of free will is not as straightforward as it seems. Even if we believe humans possess free will, what happens when it is repeatedly misused? Can it diminish over time, or even disappear altogether?

The Perspective of Maimonides

Maimonides (1138–1204), whose passing we commemorate this week, firmly believed in the near-absolute free will of human beings. In his Mishneh Torah, he writes:

"Free will is granted to all men. If one desires to turn himself to the path of good and be righteous, the choice is his. Should he desire to turn to the path of evil and be wicked, the choice is his." (Laws of Repentance)

According to Maimonides, it would be inconceivable for God to command actions and promise reward or punishment if humans could not accept or reject divine commands. Any system of law and justice assumes that people can choose freely.

Without free will, reward and punishment lose their meaning

Even today, when belief in free will has been challenged by psychology and neuroscience, we still operate under the assumption that individuals have agency over their actions. For instance, the legal defence of insanity hinges on the idea that, in certain cases, a person is incapable of making a conscious choice and thus cannot be held fully accountable. While philosophers such as Spinoza argued that determinism does not contradict moral responsibility, the prevailing view remains that free choice is essential to justice and accountability.

Pharaoh's Hardened Heart—A Challenge to Free Will

The question of free will arises prominently in Parashat Va’Eira, where God declares:

“But I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, I will multiply my signs and wonders in the land of Egypt. Pharaoh will not listen to you, and I will lay My hand upon Egypt and bring out My armies, My people, the Israelites, from the land of Egypt with great judgments.” (Exodus 7:3-4)

If God hardened Pharaoh’s heart, how can the subsequent punishments be justified? If Pharaoh’s free will was overridden, is he truly to blame for his actions?

Maimonides addresses this dilemma in Eight Chapters, his introduction to Pirkei Avot:

“Pharaoh and his followers, by their own free will, without any external compulsion, chose to oppress the strangers among them... The punishment which God then inflicted upon them was that He withheld from them the power of repentance, ensuring that justice was served for their prior misdeeds.”

Pharaoh and the Egyptians enslaved the Israelites with brutal labor and even resorted to infanticide before the plagues began. The plagues, then, were a just punishment. The temporary hardening of Pharaoh’s heart was not an arbitrary act of divine intervention but rather part of the consequences he and his people had already brought upon themselves.

Repeated wrongdoing can lead to a loss of the ability to choose differently

The Gradual Loss of Free Will

Taking Maimonides’ interpretation a step further, we can view Pharaoh’s loss of free will not as a sudden, supernatural event, but as a natural consequence of his repeated choices. There are behaviors that, when indulged repeatedly, harden the heart and diminish the capacity for change.

Aristotle addressed this phenomenon in the following way:

"At first, it is within a person’s power not to become unjust or licentious. But once they have become so, it is no longer within their power to be otherwise."

Erich Fromm, in his book You Shall Be as Gods, applies this idea to Pharaoh:

"Every evil act tends to harden the heart, while every good act makes it more alive. The more a person’s heart hardens, the less they can change freely, and the more they are driven by

their past choices."

Thus, Pharaoh's hardened heart reflects a universal truth—bad habits, when reinforced over time, can lead to a loss of control and freedom.

Free will is not static; it requires constant effort to maintain

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks: Free Will as an Effort

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks offers a compelling reversal of this concept. He argues that free will is not a given state, but something that must be actively cultivated. If a person does not exercise their freedom, they risk losing it.

"Freedom is neither given nor absolute; we have to work for it," writes Rabbi Sacks in Judaism’s Life-Changing Ideas. He notes that people can lose their freedom through

destructive behaviors—whether it be Pharaoh's tyranny, or modern-day addictions to substances or technology.

According to Rabbi Sacks, the ability to choose is a skill that requires constant effort. If neglected, free will atrophies, and a person may find themselves acting compulsively rather than making deliberate choices. To avoid this, one must actively cultivate positive habits and moral decision-making.

Conclusion: A Timeless Lesson on Free Will

The story of Pharaoh’s hardened heart teaches us a profound lesson about human nature. While free will is a powerful gift, it is also fragile. Misuse can erode it over time, leading to a loss of agency and accountability. Whether through ancient texts or modern psychology, the message remains the same: we must consciously nurture our ability to choose good, lest we find ourselves unable to do so when it matters most.

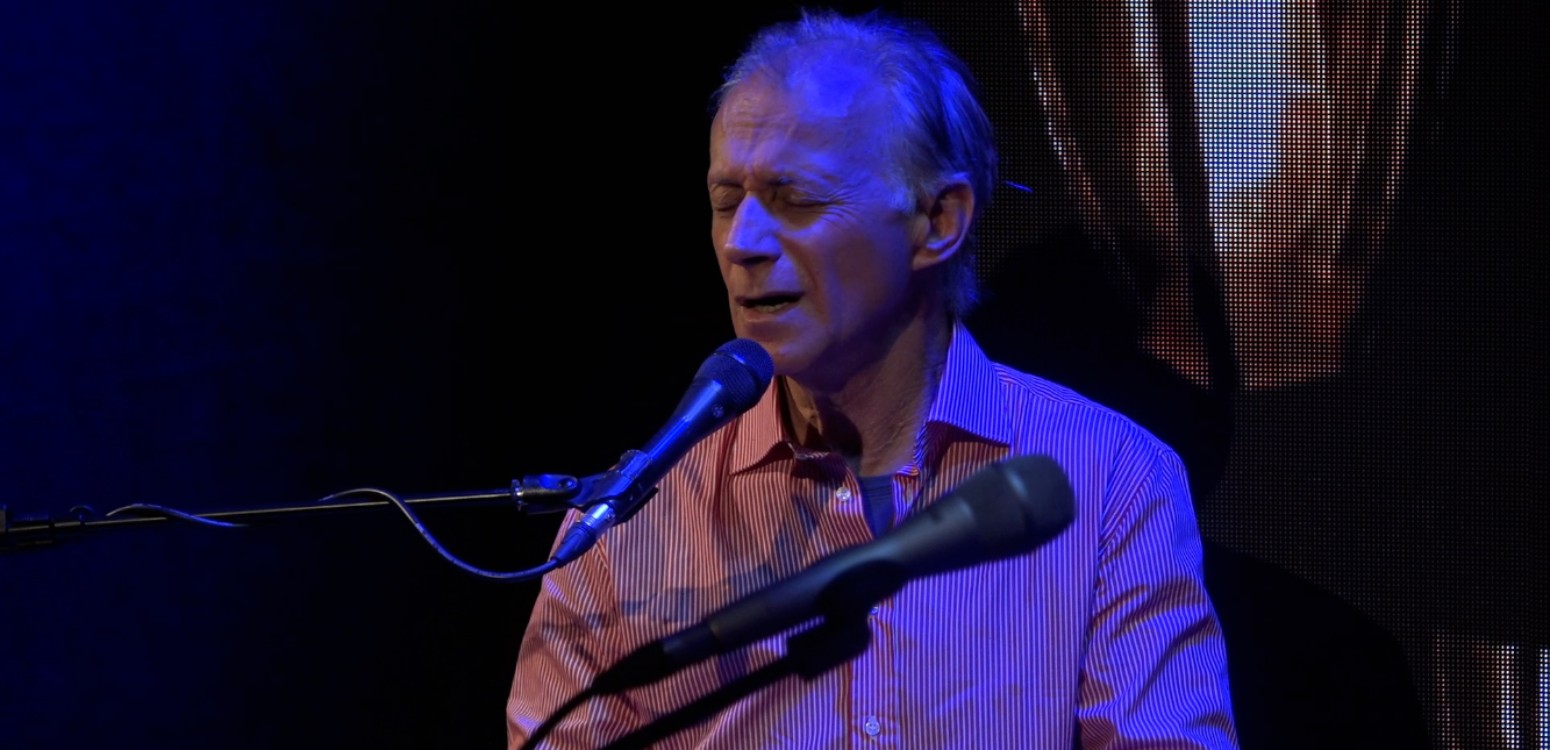

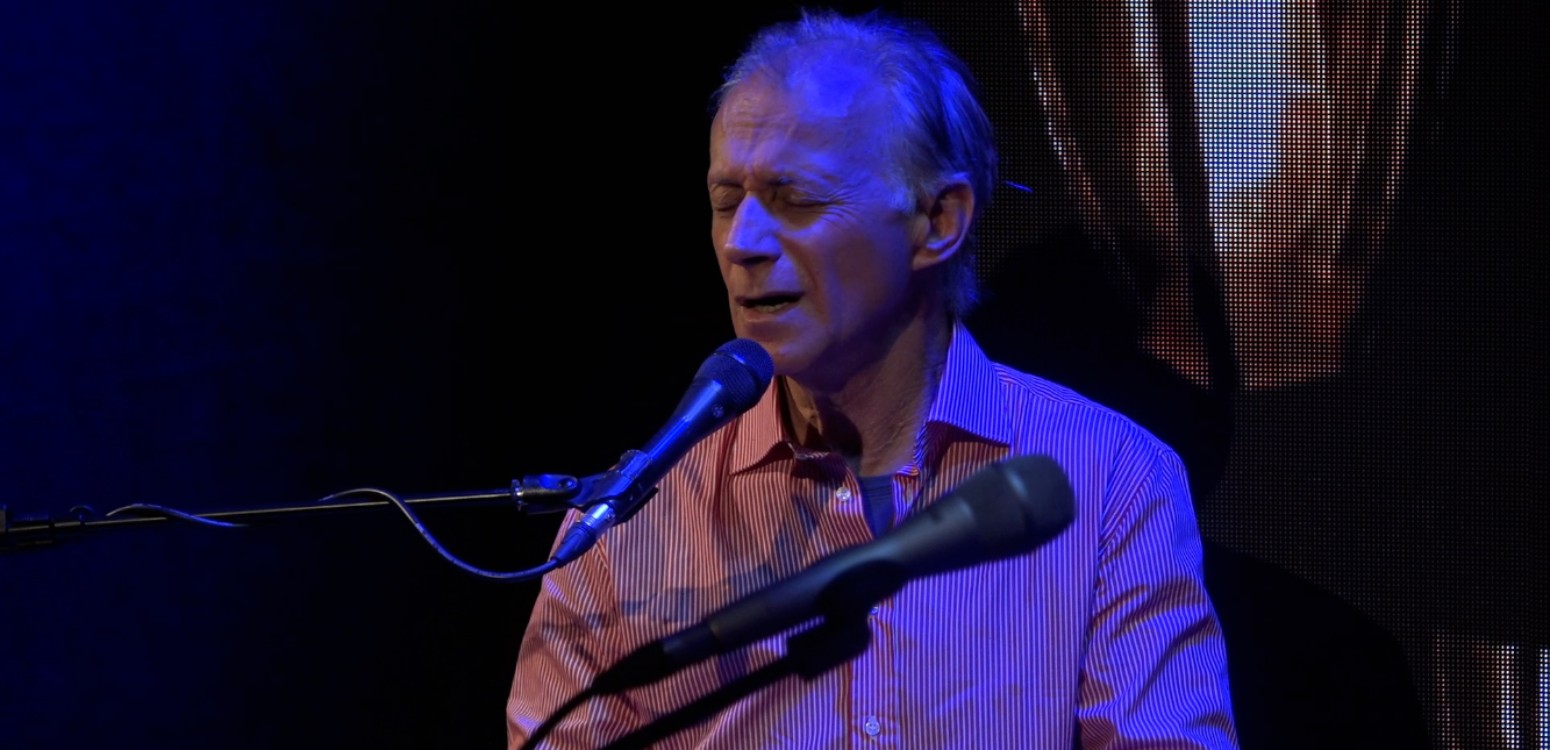

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of What Is Above, What Is Below (Carmel, 2022). He is the host of the daily Source of Inspiration podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Va’Eira, listen to Beit Avi Chai’s Source of Inspiration podcast (in Hebrew).

Main Photo: Aaron's Rod Changed to a Serpent, illustration from the 1890 Holman Bible\ Wikipedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai