The Diwan, a cornerstone of Yemenite culture, is a cherished collection of paraliturgical poems sung during Shabbat, holidays, and celebrations. Today, dedicated enthusiasts in Israel strive to preserve this rich tradition for future generations

If your roots are nowhere near Aden or Sana’a, you’ve probably never heard of the Yemenite Diwan. It is a paraliturgical collection of poems of the Yemenite Jewry. This poetry stems from the poetry of the Spanish Golden Age (1492 - 1700) and Yemenite Muslim poetry. As for its name, diwan is a Persian word. It was ended up entering the Arabic language, and in Arabic it means a collection of poems by the same poet. In Yemen, it became a name for a collection of poems and piyyutim, even though it is an anthology of many different poets.

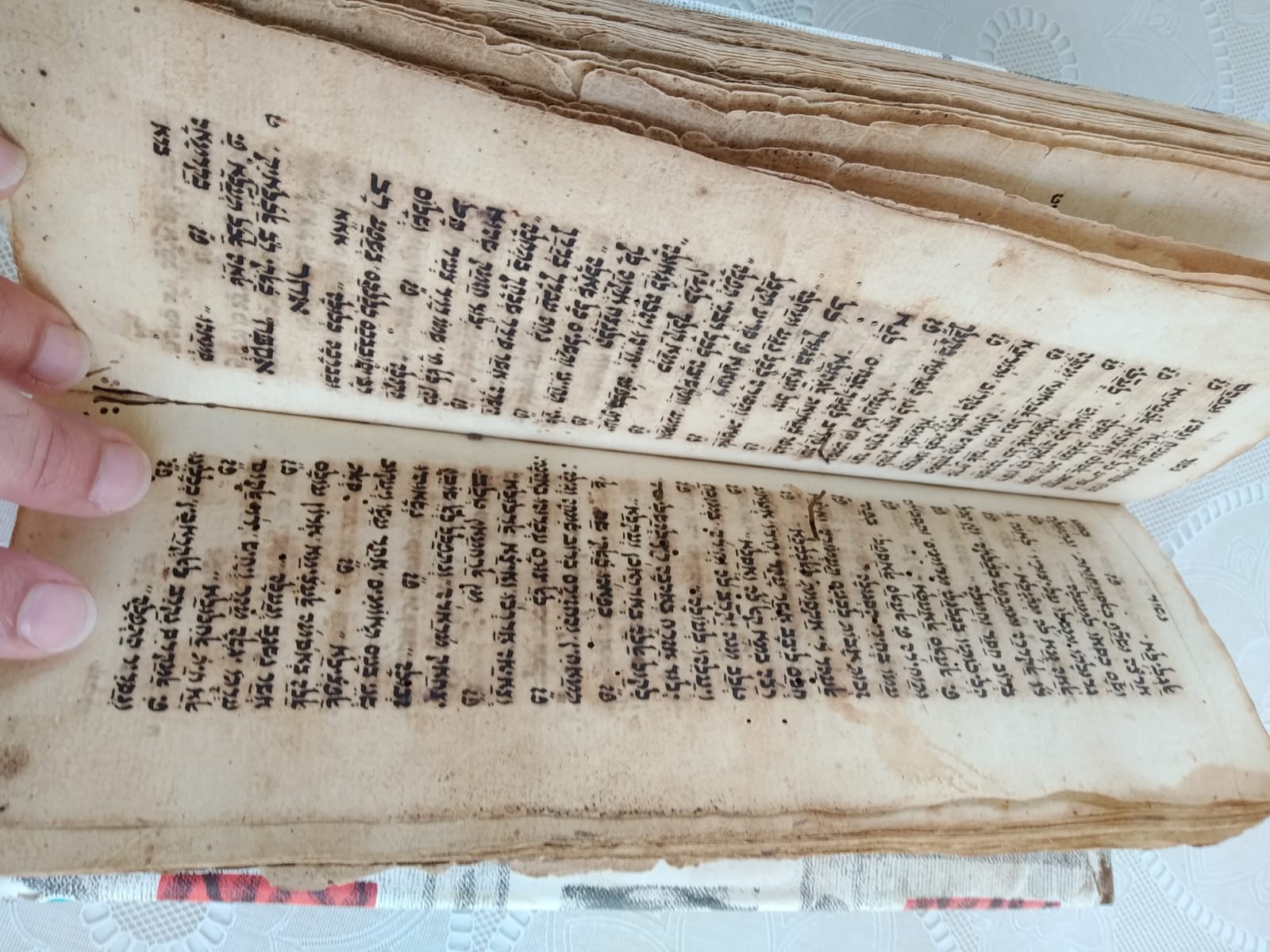

“There is a Diwan of poetry by poets of the Golden Age in Spain, for example the Diwan of Rabbi Yehuda Halevi,” explains folklore researcher Dr. Tom Fogel, who specializes in the history and culture of Yemenite Jews. “However, in the Yemenite context the uniqueness is that it is a collection of poems written in Hebrew script but in three languages: Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic. On the one hand, the poems are sacred poems, but they are not intended for the synagogue but accompany the Jewish cycle of life. These are poems for Shabbat, for the holidays, poems for occasions such as circumcision, and especially for weddings. Yemenite Jews sing these poems at home and during social celebrations. There are many manuscripts of Diwans that differ greatly from each other in terms of the collection of poems in them, and only a small portion of them have been printed.”

As for the melodies, this is an oral tradition, and therefore there are many possible melodies for one text, and vice versa – many possible texts for one melody. “Those who are familiar with the tradition can sometimes match a melody to an unfamiliar text, because they recognize the rhythmic structure of the poem,” says Fogel. “Because the melodies are an oral tradition, they have changed constantly from performer to performer, according to abilities, talent, and circumstances. Some poems were also composed in Israel by contemporary composers and turned into modern songs, by Zohar Argov for instance.”

A Deep Symbiosis with the Environment

Jewish communities in Islamic countries have had long-standing contact with the tradition of poetry. “I think the incentive for Jewish poets was to show that they could write in Hebrew no less beautifully than Arab poets,” says Fogel. “Jewish-Yemenite poetry is clearly a descendant of the poetry of the Golden Age in Spain, in the sense that the first Jewish-Yemenite poets wrote using the patterns developed by Spanish poets.

“Members of the Yemenite Shabazi family, in the generation before the famous Rabbi Shalom Shabazi, began writing poetry in the XVII century. They wrote under the influence of the poets of Spain, but they were also influenced by Arab poets in Yemen.”

Rabbi Shalom Shabazi is one of the greatest Jewish poets of all time. He is known as the greatest of Yemenite poets and intellectuals, and he is certainly the most influential of them. “Shabazi is the Jewish poet who wrote the most poems in Arabic, out of a deep symbiosis with the environment. As a poet, his ability to write poems in Arabic and pour Jewish content into them, to give Arabic terms a Kabbalistic meaning, is amazing.”

What do you think people perhaps don’t know about him?

“There are many legends about him: that he knew practical Kabbalah, that he was a kind of healer among his community, that he had magical battles with the Muslim opponent who lived in his area. Lately, I’ve been researching a manuscript of his with all sorts of prescriptions for amulets.”

Academia discovers the Yemenite Jews

Tom Fogel grew up with the tradition of the Yemenite Diwan. “My maternal grandparents immigrated from Yemen, and in my youth, I was very drawn to hearing these poems,” he shares. “I heard them at synagogue events, and around the age of 17 I started going to a class that taught these songs in Ganei Tikva, near where I grew up. As I grew older, I continued to research the subject. My family came from a peripheral area in southern Yemen, and I wanted to know more about the local singing tradition, so I went to the sound archive at the National Library, and with the help of the researchers there I came across recordings from that region.”

Fogel wrote his doctoral thesis on Shelomo Dov Goitein’s research of Yemenite Jews. Goitein was a German-Jewish historian and Arabist who researched Jewish life in the Islamic Middle Ages, and focused, among other things, on Yemenite Jewry. “Goitein turned studying Yemenite Jews into a field of academic research,” explains Fogel. “Like other German Arabists, Goitein had an amazing command of languages, which creates an incredible intimacy in this kind of research. I have recordings of him talking to people from Yemen, and you can hear his meticulousness in both Arabic and Hebrew. This helped him understand the culture in a way that sometimes anthropologists aren’t able to.”

How did Goitein influence your research and what is different about your work in the field?

“My research is mostly on folk culture, so I’m very interested in what Goteindid. But what interests me about these materials is what they say in a broad sense about culture and how they point to contacts between Jews and Muslims in Yemen.”

Yemeni Diwan: The Comeback

The tradition of singing and chanting poems from the Yemenite Diwan is an old one, but it continues today in the Yemenite community at Shabbat meals, weddings, and various gatherings. “Praying in a Yemenite synagogue is a very powerful experience because these are songs which the entire congregation sings together, literally verse by verse, and it really lifts you up,” describes Fogel. “In the last 15 years, there has been a revival of the piyyut in Israel, and I was also part of this trend. Today, the Diwan tradition has broken through the boundaries of the Yemenite community. There are events that appeal to the general public, for example, events I did in collaboration with my good friend Jonathan Vadai, the owner of “Carousela” and “Bab Al Yemen” (well-known cafes in Jerusalem that are also cultural institutions). We called these events Ja’ala, and we would both sing and discuss the tradition.”

What is the difference between the Diwan tradition in Yemen and in Israel?

“Firstly, the time that was dedicated to singing in Yemen was very long. A wedding took seven days, so there were seven entire evenings to fill with singing. Therefore, there are a lot of long poems, with very many verses. In Israel, over the years, the whole thing has become much shorter. Today, usually a very small part of the poem is sung.

“Another difference is the language. Most of the poems were written either in Judeo-Arabic or in a combination of Hebrew and Arabic, and today in Israel, less people are familiar with this. Less people sing Arabic verses or poems that are written only in Judeo-Arabic. Even in Yemen, ordinary people did not always understand what these poems were about, because they were allegorical and also written in a high register. This is why this poetry requires commentary and interpretation.”

Is it correct to say that the Yemenite Diwan was “discovered”?

“The Diwan was ‘discovered’ for the world of research; Yemenite Jews did not have to discover it. Jewish scholars in Europe collected Jewish poetry from Spain, and in this way many Yemenite manuscripts containing poems by poets of the Golden Age reached Europe. For researchers, it was a treasure.

“The first to address the Yemenite Diwan in a research-based and serious manner was probably the ethnomusicologist Abraham Zevi Idelsohn, who wrote a book on the tradition of Diwan poetry based on recordings and interviews he conducted in Jerusalem with immigrants from Yemen at the beginning of the XX century.”

Is the Yemenite Diwan in danger of disappearing and being forgotten?

“There is such a danger. Some of the texts are with us as manuscripts, but the Yemenite Diwan is mainly an oral culture, part of which has already been lost because most of the people who immigrated from Yemen are no longer with us. In terms of written texts – the ability to understand and read them is something that requires learning. In Yemen, part of the tradition was both to sing the songs and to interpret them. The danger of extinction also stems from the performance aspect. Yemen is a very large and culturally diverse country, and each region had different traditions of performance. A few years ago, I interviewed a person who said that there is no recording from the place he came from in Yemen, and the five melodies I recorded him singing are the only documentation that exists from that area.”

The good news is that poems from the Diwan and melodies continue to be discovered. “Recently, Professor Joseph Tobi, one of the leading researchers in the field, published the first volume of a scientific edition of Shabazi’s poems. In recent years, he has found several more poems by Shabazi in the poet’s handwriting. Some of these manuscripts lie in drawers in people’s homes, and once in a while an unknown poem is discovered.”

Dr. Tom Fogel is a folklore researcher, focusing on the history and culture of Yemenite Jews. He is a research associate in the Department of Jewish History at Tel Aviv University and teaches at Achva Academic College.

Main Photo: A segment from a w:Tiklal prayerbook authored by Shabazi himself, in his own hand. 1676.\ Wikipedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai