The Torah’s ritual of the Sotah – where a woman suspected of adultery must drink a mixture with supernatural characteristics – represents one of scripture’s most disturbing passages. This ancient trial by ordeal forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about jealousy, patriarchy, and the persistence of domestic violence from biblical times till today

This week we confront one of Torah’s most troubling passages: the ritual of the Sotah. When a husband suspects his wife of adultery and she denies it, ancient Jewish law prescribed an extraordinary ceremony. The jealous husband brings his wife before the priest with an offering of barley flour. The priest prepares holy water in a clay vessel, mixing dust from the Tabernacle floor into it, uncovers the woman’s head in humiliation, and places the offering in her hands.

Standing before the priest, the suspected woman must listen as he pronounces these chilling words:

“‘If no other party has lain with you, if you have not gone astray in defilement while living in your husband’s household, be immune to harm from this water of bitterness that induces the spell. But if you have gone astray while living in your husband’s household and have defiled yourself, if any party other than your husband has had carnal relations with you’ – here the priest shall administer the curse of adjuration to the woman, as the priest goes on to say to the woman – ‘may the Lord make you a curse and an imprecation among your people, as the Lord causes your thigh to sag and your belly to distend; may this water that induces the spell enter your body, causing the belly to distend and the thigh to sag.’ And the woman shall say, ‘Amen, amen!’” (Numbers 5:19–22)

Supernatural jurisprudence

The woman then drinks the mixture. If she is innocent, no harm is done to her, yet guilt triggers miraculous punishment – her body suffers the very deformities described in the priest’s curse.

What makes this ritual uniquely puzzling is its supernatural element. As Ramban notes: “There is nothing amongst all the ordinances of the Torah which depends upon a miracle.” Yet here, divine intervention determines legal reality.

Professor Jacob Licht’s research reveals that such trials by ordeal were widespread in ancient cultures, typically involving physical harm – holding red-hot iron, for instance, with guilt or innocence determined by how wounds healed. The Sotah ritual fits this broader pattern of supernatural jurisprudence.

Channelling rage into ritual

The rabbis tried to refine this troubling ritual. They required the husband to first warn his wife publicly, with witnesses, before proceeding. They even gave women an escape route – she could refuse the ordeal and divorce her husband, though she'd forfeit her ketubah.

But other rabbinic modifications made things worse. As Professor Ruhama Weiss documents, they transformed a private ritual into public spectacle: the woman was stripped naked before the entire community, her jewelry removed, clothes torn, body examined and humiliated in ways that “reflect violent sexual fantasies toward women.”

I’ll be honest – sometimes our scripture is difficult to read. This ritual embodies everything we now recognize as toxic: a patriarchal system where women are property, where men are “masters” with multiple wives while women belong to one husband, where male suspicion alone can destroy a woman’s dignity.

Yet even this disturbing ritual may have served a protective function. In a world where jealous husbands could privately beat or murder their wives with impunity, requiring them to bring accusations before a priest created a legal process – however flawed – that might have saved lives by channelling rage into ritual rather than violence.

Can we create better tools than our ancestors had?

This ancient battle with jealousy and domestic violence hasn’t disappeared. In Israel today, approximately 25 women are murdered annually by partners or family members, with thousands more cases of domestic violence reported each year – likely just the tip of the iceberg. The burning question remains: can we create better tools than our ancestors had?

The Sotah ritual forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth about human nature and the persistence of intimate partner violence across millennia. While we rightfully recoil from its methods, we cannot ignore its underlying recognition that unchecked jealousy kills. Our challenge is not just to condemn the past, but to build systems that protect vulnerable people today. The ancient priests offered holy water and supernatural intervention. What do we offer? And will it be enough?

In preparing this installment I was assisted by Elchanan Samet’s article “Parashat Naso” that originally appeared in the book “Studies in the Weekly Torah Portion” (Maaliyot Publishing House) and was later published on the Daat website. Professor Licht’s research was quoted in Samet’s article.

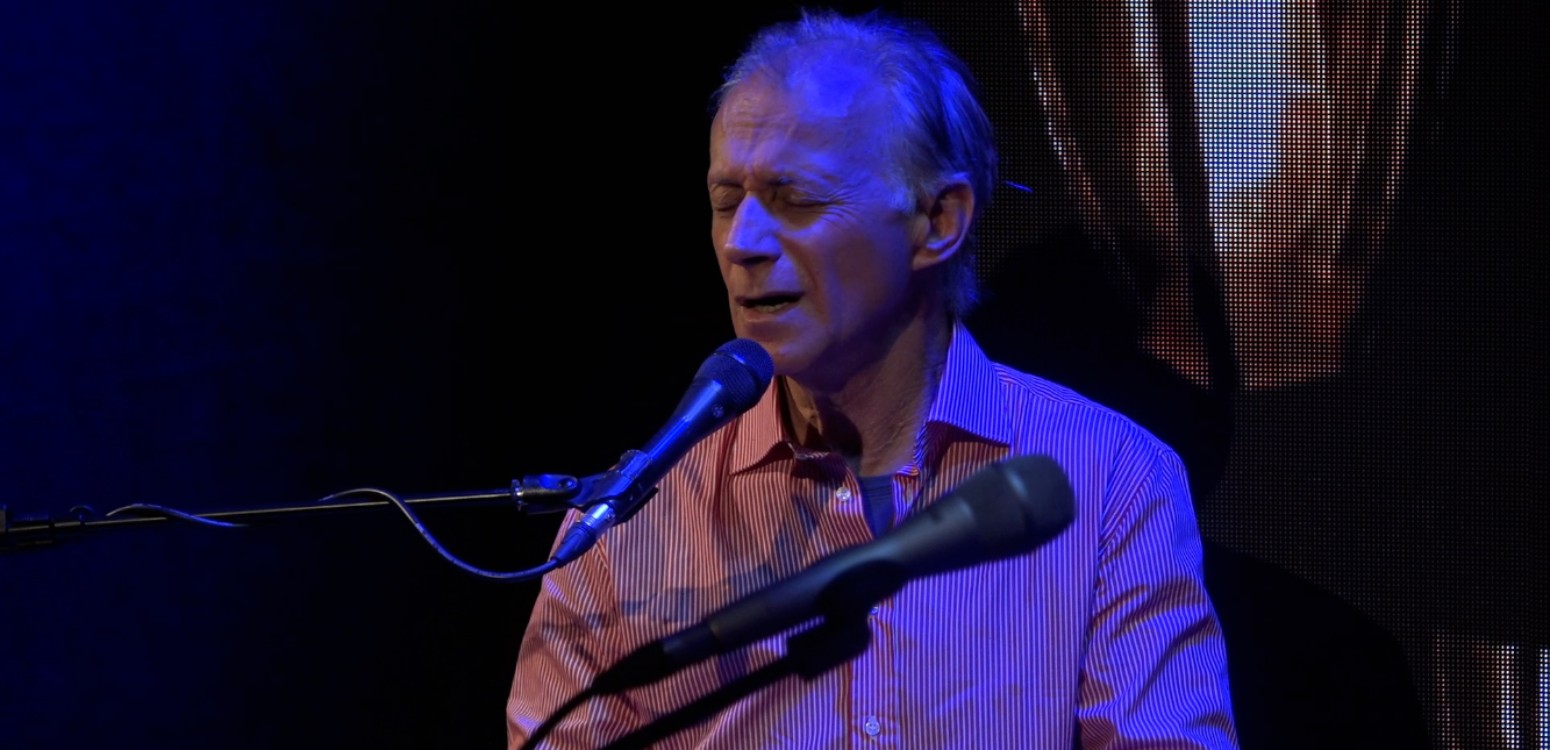

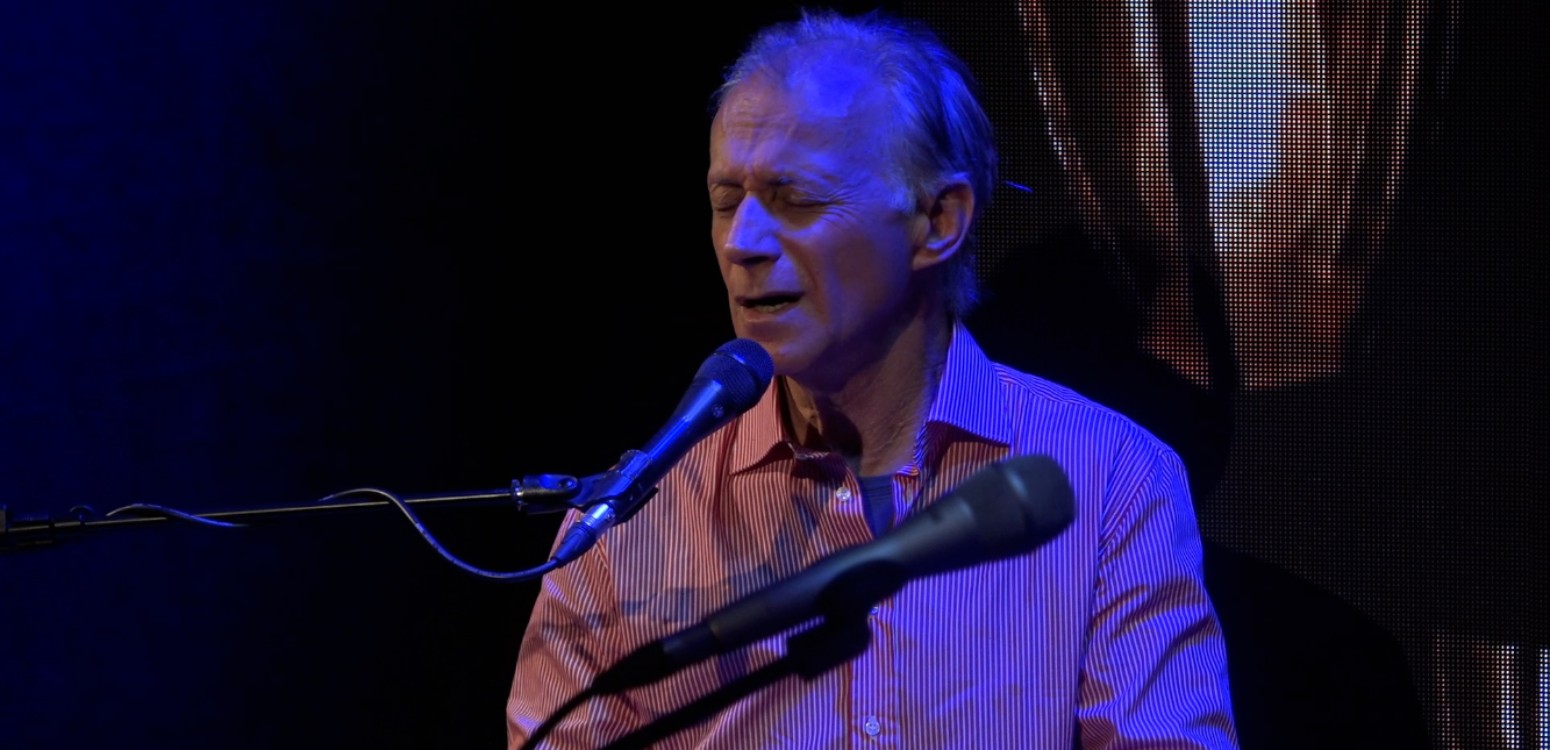

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Naso, listen to “Source of Inspiration”

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo:Created using AI

Also at Beit Avi Chai