As antisemitism surges globally, historian Dr. Asael Abelman turns to American Jewish literature for answers. From Philip Roth’s alternate histories to Cynthia Ozick’s identity struggles, these writers confront urgent questions: What do we owe our murdered ancestors? Could there be a Holocaust of American Jews? And what is the true cost of Holocaust memory?

Dr. Asael Abelman is a historian, lecturer, author, Israeli, and Jew. All of these identities converge in a lifelong, multifaceted engagement with the singular story of our people. As a reader, too, Abelman devotes himself to this story: he finds special interest, as both a man of letters and a scholar, in Jewish prose. These writers, he says, offer us detailed Jewish portraits, open a window into the spirit of various eras, and shed new light on how historical events are embedded within the long arc of Jewish memory. In his Hebrew-language online lecture series at BAC, “Shadows over the Hudson: Jewish Writings on the Holocaust and US Jewish Fate”, Abelman delved into the works of five major writers who helped give written form to this extended narrative.

A mirror of Jewish identity under trial

In turbulent and challenging moments of history, Abelman believes literature offers a uniquely valuable refuge. “At the eye of a great storm,” he says, “literature seems to be the sanest place to settle – because it’s more suggestive, and the possibilities it offers are more open.” Accordingly, in the face of Israel’s wartime questions, Abelman finds himself drawn not to local writing, but to the post-Holocaust literature of major American Jewish authors. In his view, Jewish identity in Israel – and to a great extent in the United States—is now undergoing a trial much like the one it faced in the XX century. That trial is vividly reflected in the works of Isaac Bashevis Singer (1902–1991), Cynthia Ozick (born 1928), Herman Wouk (1915–2019), Philip Roth (1933–2018), and Jonathan Safran Foer (born 1977) – the five authors at the heart of Abelman’s series.

Cynthia Ozick is one of his favorite examples, and he is currently working on a Hebrew translation of a collection of her stories. Born in 1928 in the Bronx, Ozick has often dealt in her writing with questions of roots, identity, conversion, and the costs of abandoning identity. She reflects deeply on both the experience of Jewish life in America and the nature of writing Jewish literature in English. The Holocaust appears in nearly all of her works in one way or another, generating the dilemmas she explores. In her short story collection “Levitation: Five Fictions,” one of the stories tells of a Jewish American writer married to a preacher’s daughter – but, in Abelman’s words, “even though he’s in Manhattan, all he can think about is Jews being slaughtered in Europe’s age of horrors.” For Ozick, this preoccupation with identity is inescapable.

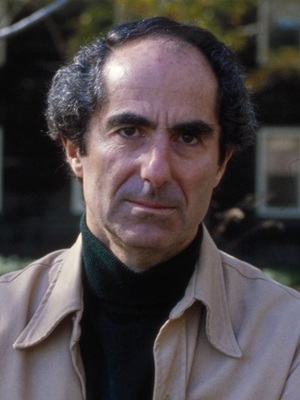

Philip Roth, the famous novelist, also dealt extensively with Jews and Judaism in his work – though his stance on its role in his writing was sharply different. Roth famously declared, “I’m not a Jewish writer; I’m a writer who is Jewish.” The statement drew Ozick’s disapproval; she responded that it expressed not a creed, but a sentence of doom. Abelman points out, however, that Roth’s literary profile undermines the clear-cut dichotomy he sought to assert. Roth’s books are saturated with Jewish characters, Jewish dilemmas, and deep reflections on Jewish identity and even the relationship to the State of Israel. According to Abelman, one of Roth’s most important literary achievements, featured in his novel The Plot Against America is his portrait of the American Yiddishe Mame. “It’s a wonderful character,” says Abelman, “a middle-class American Jewish woman who becomes a moral anchor, maternal and even exemplary in her simplicity.”

Another writer close to Abelman’s heart is Isaac Bashevis Singer, whom he describes as “an astonishing figure, both biographically and artistically.” Singer left his father’s strict Jewish home in Eastern Europe and never looked back on that religious way of life. “He denied himself no pleasure imaginable,” says Abelman, “and yet he remained convinced that no human being in history – not even the Buddha – reached the moral level of his father.” His father, who Abelman calls “a four-cubit Jew” – that is, a diasporic, rabbinic Jew – was, to Singer, the most radiant human achievement imaginable.

Caught between recent European history on the one hand and the alternative of Hebrew-speaking Judaism on the other, these writers consistently raise a series of searing questions. When asked to articulate them, Abelman replies: “What does it actually mean to be Jewish in America? What do we owe the ancestors from Eastern Europe who were murdered? Are our lives now what they hoped for? Are we betraying them? And hardest of all – yet unavoidable – what is the price of memorializing the Holocaust?”

Jews living outside the Holocaust museum

That last question, says Abelman, underscores the unique importance of reading “living” Jewish literature – works with a pulse that directly confront Jewish concerns. The sharp, alert voices that emerge from these works offer a powerful alternative to one of the most dominant forms of Jewish representation today: Holocaust museums. Abelman points to a certain addictive quality in the narrative crafted by such memorial institutions and invokes the work of Jewish-American author Dara Horn (born 1977), “People Love Dead Jews.” He references Horn’s suggestion that there may be something seductive in the notion that the natural home of the Jew is the Holocaust museum. “It’s no coincidence,” he says, “that a million people visit the Anne Frank House every year. And if you have endless Holocaust museums, people may come to believe that this is what a Jew looks like.” This alluring idea – that the ideal Jewish existence is that of the dead Jews of the past – can even infiltrate the consciousness of Jews themselves.

2.jpg)

Jonathan Safran Foer, in his novel “Everything Is Illuminated,” captures a piece of this mentality. The book follows its protagonist – a version of Foer himself – on a journey to a town in Eastern Europe where his ancestors lived before the Holocaust. In his search for the woman who saved his grandfather, he encounters the memory of the lost Jewish community. Abelman describes the scene as a disturbing encounter between Foer’s fictional alter ego and “beautiful Jews – beautiful in the fact that they are dead.”

Nevertheless, in Safran Foer’s work – as in that of the other authors in the series – the question of antisemitism plays a central role. “All of them ask why Jews are hated and murdered,” Abelman says, “and that leads to another recurring question: could there be a Holocaust of American Jews?” Roth raises this possibility with striking vividness in The Plot Against America, depicting an alternate American history that descends into antisemitism and Nazism. His American Jews behave with the same naiveté as European Jews before the war and bring disaster upon themselves. Reading Roth, and the other texts discussed in the series, becomes all the more urgent in light of the current wave of renewed antisemitism.

And precisely because these questions are so urgent today, Abelman insists, literature offers a vital lens through which to examine them. “It’s worth reading these works,” he says, “to encourage ourselves to escape the filthy froth of current politics and try to understand what’s really going on, in depth. Maybe I’m naïve, but I still believe literature hasn’t lost its power to sharpen that kind of understanding.”

Main Photo: Jewish war veterans march on the State Capitol to protest treatment of displaced European Jews, St. Paul\ Wikipedia