When desperate words become sacred bonds, the consequences can be devastating. From Jephthah’s tragic sacrifice to the rabbis’ revolutionary annulment mechanisms, this exploration of biblical vows reveals profound questions about identity, transformation, and the price of change. Can we truly become new people – and if so, what do we owe our former selves?

We’ve all been there: backed into a corner, facing an impossible situation, and suddenly the words tumble out: “God, if you just help me through this, I swear I'll...” These bargaining prayers, born from desperation, tap into one of humanity’s oldest and most dangerous spiritual technologies: the vow. This week’s Torah portion reminds us why our ancestors both revered and feared the power of sacred promises:

“If a man vow a vow to the Lord, or swear an oath to bind his soul with a bond; he shall not break his word, he shall do according to all that proceeds out of his mouth.” (Numbers 30:3)

A foolish and reckless commitment

The Torah treats vows as sacred contracts, transforming desperate words into binding obligations. Jacob promises God a tenth of his wealth if he survives his journey. Hannah vows to dedicate her future son to divine service if she’s blessed with a child. But notice the escalation: Jacob’s vow binds only himself, while Hannah’s binds another person entirely – her unborn son.

This dangerous progression reaches its horrific climax with Jephthah the Gileadite, who makes the most reckless vow in all of Scripture:

“And Jephthah made the following vow to the Lord: ‘If You deliver the Ammonites into my hands, then whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me on my safe return from the Ammonites shall be the Lord’s and shall be offered by me as a burnt offering.’” (Judges 11:30-31)

What a foolish and reckless commitment. Jephthah surely thought a goat would come out to meet him, but when he returned home victorious, the first one to greet him was his only daughter. Jephthah, torn from within, told her about the vow, and she accepted the judgment and only asked that he give her two months to go weep over her virginity and the tragic end of her life. In the end, Jephthah fulfilled his terrible vow.

The enormous tension that exists within the mechanism of a vow is revealed here in all its horror. On the one hand, it is a wonderful mechanism of speech that gives power and honor to words; on the other hand, vows are often made out of distress, when a person’s mind is not entirely clear, and the result can be tragic.

How to annul a vow?

The Sages and a number of halachic authorities were troubled by this and tried to convince us not to make vows at all. Shulchan Aruch even calls one who makes vows a sinner (Yoreh De’ah 203:1). In addition, the Sages caused a revolution in the field by inventing a mechanism for annulling vows.

The Sages created two escape routes from the prison of vows. The first, petach (“opening”), is based on new information: “If I had known this would happen, I never would have made the vow.” Had Jephthah lived centuries later, this mechanism could have saved his daughter’s life.

The second route, charata (“regret”), is more radical. Here, the vow-maker admits: “I meant what I said then, but I deeply regret it now.” One is about discovering new facts; the other is about becoming a new person.

Understandably, the rabbis were wary of regret-based annulment. After all, anyone could simply declare “Oops, I regret it” and escape their commitments. But buried within this mechanism lies a profound insight about human identity and the possibility of genuine transformation.

The old self was bound by the vow; the new self never made it at all

When someone seeks to annul a vow through regret, they’re making a startling claim: “The person who made that promise no longer exists.” The old self was bound by the vow; the new self never made it at all.

This ancient legal concept forces us to grapple with transformation itself. We all know the experience of fundamental change – moments when we look back at our former selves with bewilderment or even shame. The rabbis understood that people can undergo such profound shifts that they become, in essence, different individuals.

Their recognition that regret can nullify sacred vows offers a powerful lens for understanding forgiveness. When someone who has genuinely transformed seeks absolution for their former self’s actions, we face a profound dilemma: if they have truly become a new person, do their old debts die with their old self, or must the new person still pay the price for what came before?

The ancient wisdom of vow annulment suggests that the answer, like human nature itself, is beautifully and frustratingly complex.

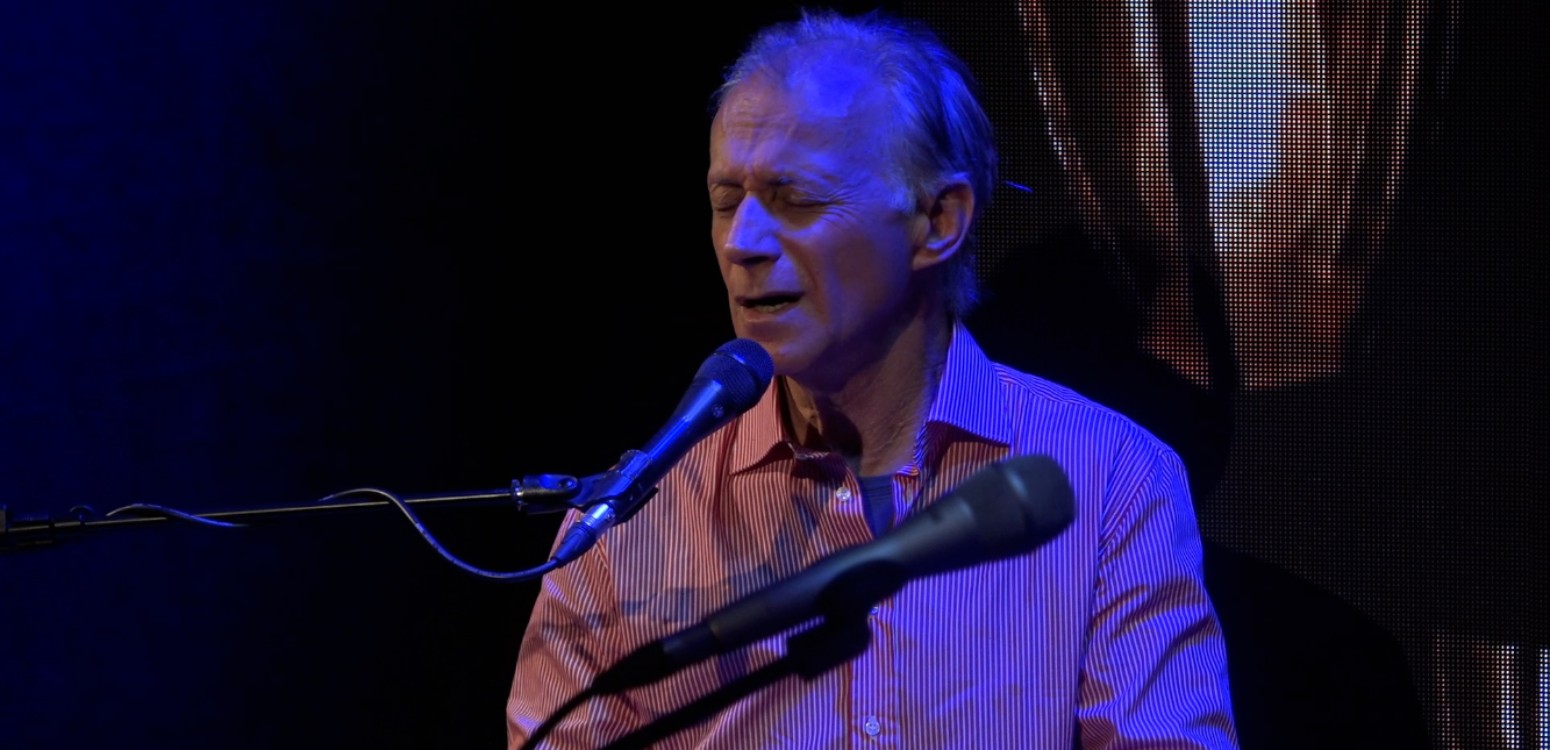

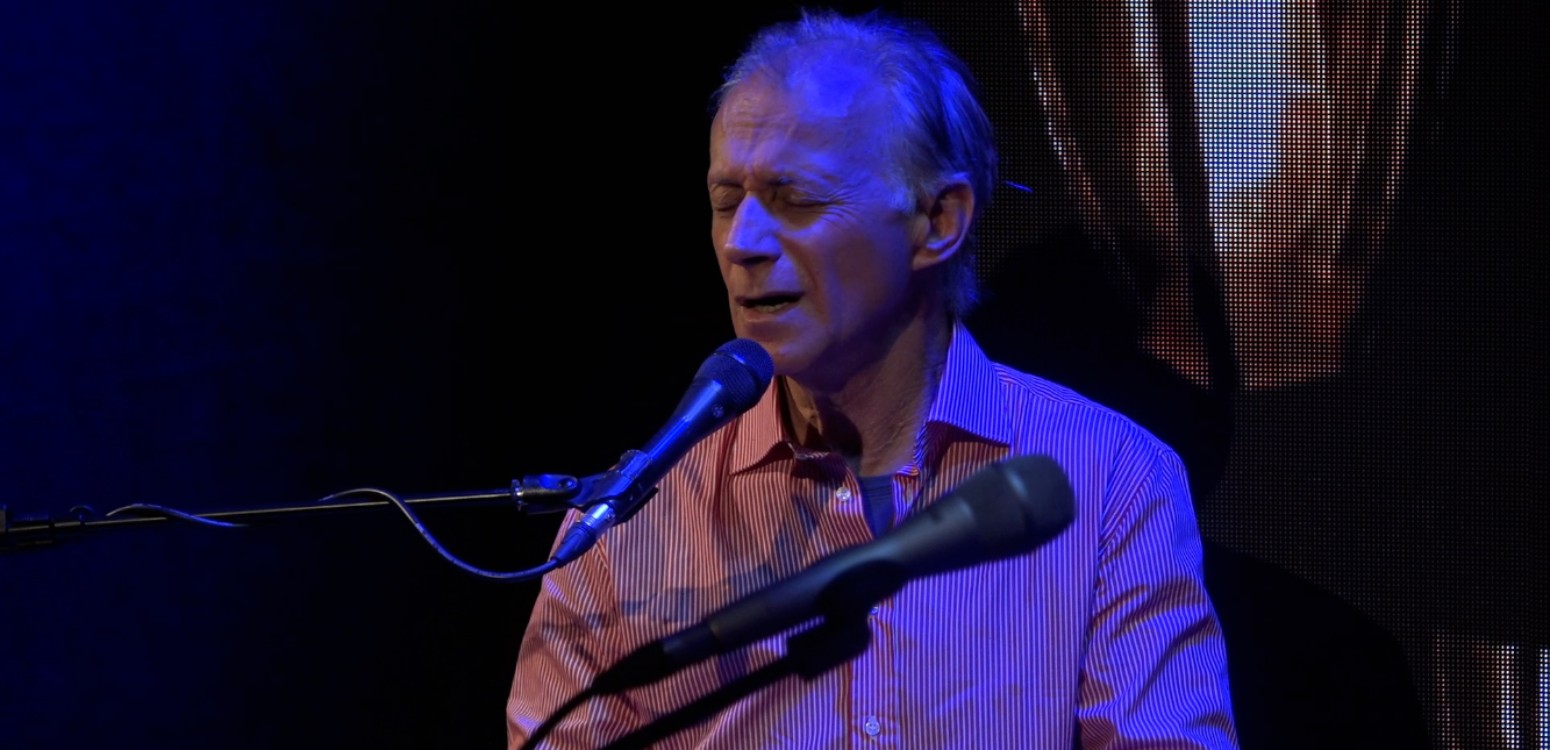

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Matot, listen to “Source of Inspiration”>>

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo:Created using AI

Also at Beit Avi Chai