The first verse in the Book of Deuteronomy marks Moses’ transition from a vessel of God’s speech to a man of his own words – and therefore, a leader.

The opening of the Book of Deuteronomy is a curious one. “These are the words that Moses addressed to all Israel on the other side of the Jordan. – Through the wilderness, in the Arabah near Suph, between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Hazeroth, and Di-zahab” (Deuteronomy 1:1). This verse is surprising, because in the three preceding books – Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers - Moses served as a kind of conduit for the word of God; the verse “And the Lord said to Moses” was repeated again and again. Deuteronomy, for its part, is essentially a long speech by Moses. When he reaches the end of his days, a revolution occurs: he now speaks in his own words.

Moses’ transition from vessel to leader was a very successful one. According to Yeshayahu Leibowitz, the impact of the words that God spoke directly to the Israelites, even through Moses, lasted only a few days. That was certainly the case at Mount Sinai, as the end result was the Golden Calf. In comparison, Moses’ words of leadership in the Book of Deuteronomy have a more lasting impact. They lead to the verse “While you, who held fast to your God, are all alive today” (Deuteronomy 4:4). On this matter, Leibowitz offers a radical quote from the Midrash Hagadol that says: “The Lord said to Moses: ‘Since Israel has cleaved to Me through these words, they shall be called only by your name’, as it says: ‘These are the words that Moses spoke to all Israel’; it does not say ‘that the Lord spoke,’ but rather: ‘that Moses spoke.’”

The crux of faith

According to Leibowitz, these midrashic words reveal the crux of the meaning of faith: that ‘these words’ from the mouth of the Almighty were not nearly as effective as Moses’ words ‘that he spoke to all Israel’ – the latter were the ones that brought Israel to cleave to Him – and that faith can never come except from man himself. Leibowitz goes on: Moses the man, born of woman, is at the center of accepting the yoke of the kingdom of heaven and the yoke of Torah and commandments. Only through his own powers and his own ethical decision, not through divine intervention, can a person know God and cleave to Him.

Here, Leibowitz expresses a bold theological idea that stems from a general claim about the human soul: that a person’s ethical decision can come only from within. The failure of divine revelation, and in contrast the success of Moses’ speech, teach us that it is impossible to impose an ethical decision on a person, not even through explicit miracles. Even the service of God, like any other ethical decision, depends on the human and not the divine.

Leibowitz goes on to say that these midrashic words hint at the great idea about the superiority of the Oral Torah, which is entirely the work of human hands, over the heavenly Written Torah. As Moses claims before Israel, the words of the Torah that are uttered and learned by human beings are more powerful than divine revelation.

A man of words

And there is another revolution in this opening of our parasha. Moses now presents himself as a man of words, despite having claimed some forty years earlier before God: “Please, O my lord, I have never been a man of words, either in times past or now that You have spoken to Your servant; I am slow of speech and slow of tongue” (Exodus 4:10). Deep knowledge of Torah and his life experience as a leader changed Moses. Here lies a simple and important message: before you study, know, and truly understand, you must see yourself as slow of speech and slow of tongue. Humility demands that a person not be “a man of words” before having well-founded, substantial things to say.

There are leaders who are preoccupied mainly with talk and less so with action. They dedicate a considerable part of their time and energy to public relations and believe that the essence of leadership is speech. Conversely, leaders like Moses speak only at the end, after having acted and learned.

These words have great relevance to our times, particularly to the fast-approaching eve of Tisha B’Av. We live in an era filled with chatter, amid which Moses’ words of substance stand out. Now, more than ever, we can appreciate the importance of the existence of a conduit, a kind of filtering and amplification system for the words of others, until the moment comes and we can say words of substance of our own. There is a deep connection between the act of airing empty words – words that often invoke hatred, shallowness, vanity – and destruction. However, renouncing oneself is not the answer either. Moses too knew during his lifetime to sometimes intervene in God’s words with his own. This constitutes, rather, a wish and an expression of hope that we will succeed in knowing when to be slow-tongued messengers and when to be people of words.

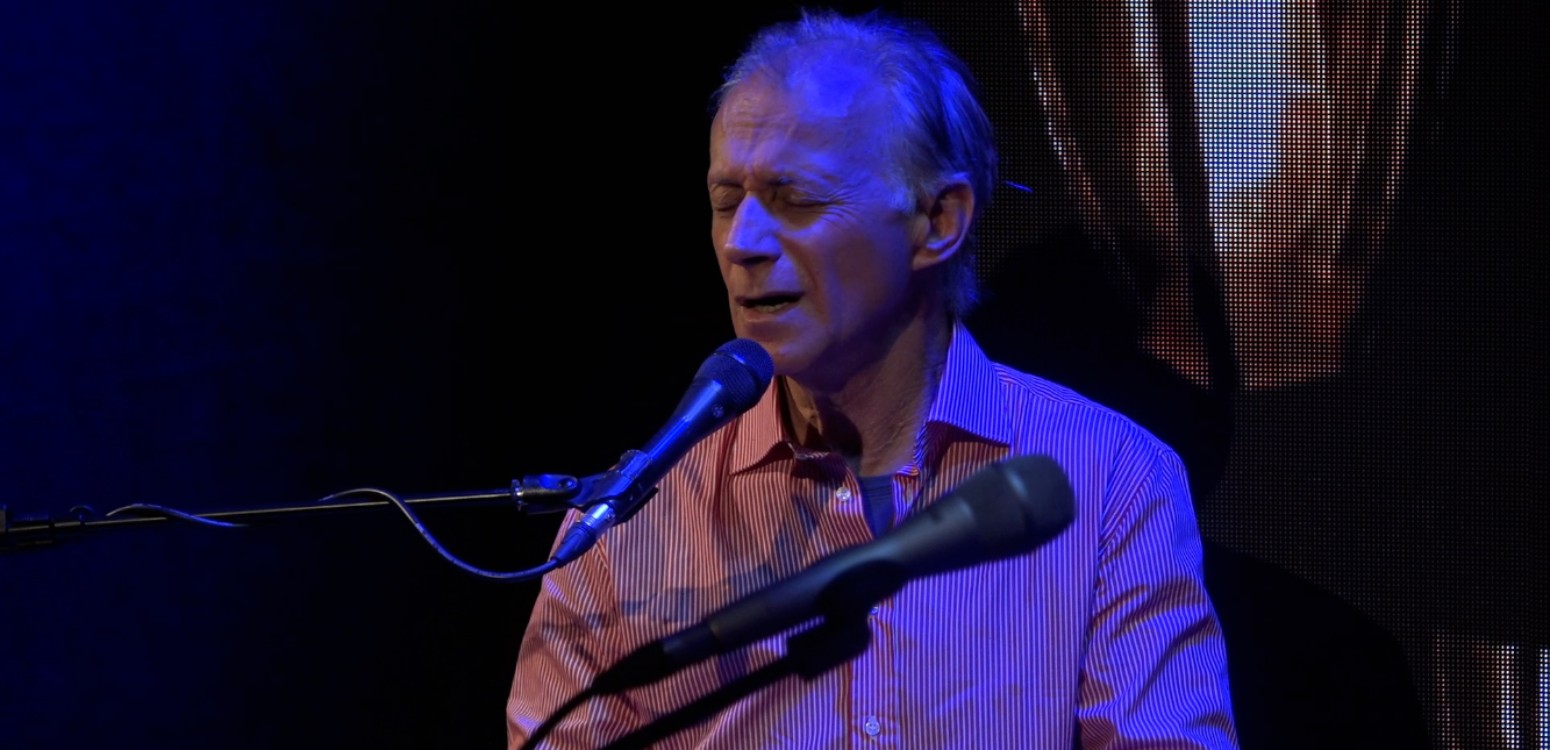

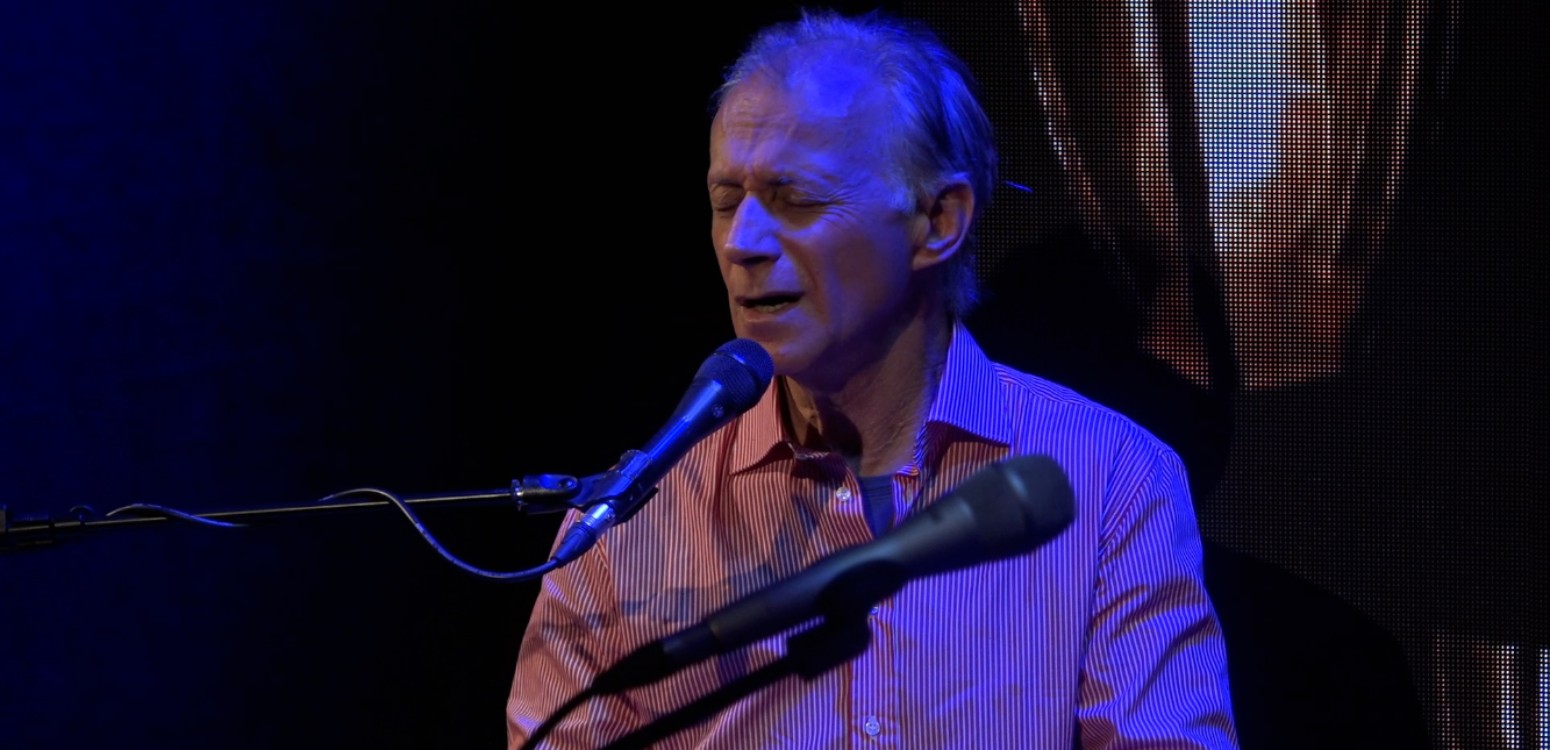

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Devarim, listen to “Source of Inspiration”

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo:Created using AI

Also at Beit Avi Chai