On the eve of entering the Land of Israel, Moses evokes the memory of slavery to issue a warning to the people of Israel: Do not become a new Egypt

What will become of a people who comes out of Egypt, from the house of bondage, walks in the wilderness for forty years, then has to fight in difficult wars, and finally becomes sovereign? Will they become Egypt themselves, that is, transform from enslaved to enslaver, or will they establish a different kind of sovereignty, a more just one?

This question preoccupies Moses in this week’s parasha, and more broadly throughout the entire book of Deuteronomy. In one of the most dramatic moments of his speech on the eve of entering the Land of Israel, he says:

“Take care lest you forget Lord your God and fail to keep the divine commandments, rules, and laws which I enjoin upon you today. When you have eaten your fill, and have built fine houses to live in, and your herds and flocks have multiplied, and your silver and gold have increased, and everything you own has prospered, beware lest your heart grow haughty and you forget Lord your God – who freed you from the land of Egypt, the house of bondage; who led you through the great and terrible wilderness with its seraph serpents and scorpions, a parched land with no water in it, who brought forth water for you from the flinty rock; who fed you in the wilderness with manna, which your ancestors had never known, in order to test you by hardships only to benefit you in the end – and you say to yourselves, ‘My own power and the might of my own hand have won this wealth for me.’ Remember that it is Lord your God who gives you the power to get wealth, in fulfillment of the covenant made on oath with your fathers, as is still the case.” (Deuteronomy 8:11-18)

The powerful should remember powerlessness

Moses is anxious about success. Following the good path produces abundance and blessings, but these very things could lead to vanity, and then the people, in their conceit, will abandon the good path. As a consequence, they will suffer retribution, forfeit all their abundance, and even go into exile from their land. Success, therefore, will bring about its own undoing. In his book, “The Last Words of Moses” (Maggid Tanakh Companions, The Toby Press), Dr. Micah Goodman explains that Moses resorts to education and memories to prepare the people of Israel for this dangerous trap. According to Goodman, the Torah uses memory as a tool to prevent arrogance and maintain humility. He argues that when people achieve success, they should deliberately recall their past struggles and dependence on God during their time in the wilderness. This practice prevents them from attributing their achievements solely to their own abilities. Goodman explains that memory works best when it contrasts with present circumstances – the powerful should remember powerlessness, the successful should remember dependency, and those who belong should remember being outsiders.

A little humility is required

If we see God as a symbol for everything that does not depend on us, then we can interpret Moses’ words thus: precisely in moments of strength, remember the role played by chance (or providence) in your life. It was not simply only your power and the might of your hand that brought you this far. A little humility is required; even the best poker player in the world needs a good hand.

Moreover, from Moses’ perspective, God is found even in things that are clearly not God. Goodman compares this to the customary blessing over bread: “Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, who brings forth bread from the earth.” This is a strange blessing. After all, it’s clear that God doesn’t bring forth bread from the earth. He may grow wheat and barley for human labor, but humans through their work turn them into bread. Goodman sees it as an educational blessing that seeks to induce in us the feeling that everything comes from God. And why diminish the significance of human labor in this way? Because otherwise our hearts might grow haughty and we might forget.

When self-righteousness is dangerous

Moses goes one step further. He cautions against think that righteousness guarantees victory in war. “And when Lord your God has thrust them from your path, say not to yourselves, ‘Lord has enabled us to possess this land because of our virtues’; it is rather because of the wickedness of those nations that Lord is dispossessing them before you. It is not because of your virtues and your rectitude that you will be able to possess their country.” (Deuteronomy 9:4-5) Moses tries to prevent the people from lapsing into self-righteousness: it’s not your justice that won it, it’s their wickedness. According to Goodman, self-righteousness is another dangerous form of pride that can emerge alongside the illusion of power. He explains that while arrogance blinds people to their weaknesses, self-righteousness blinds them to their moral failings. When people become self-righteous, they lose the ability to recognize their own sins and shortcomings. Remembering sin, then, is intended to preempt the emergence of an improper and mistaken sense of moral superiority.

It’s fascinating to see that Herzl (1860-1904), like Moses, expressed the same concerns. He wrote: “We are no better than the rest of modern humanity [...] Freedom will make us show our fighting qualities at first.” (Theodor Herzl, “The Jewish State”. Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved August 5, 2025). Both visionaries of Jewish sovereignty feared the same things and seem to be whispering in our ears now: Are you up for the challenge?

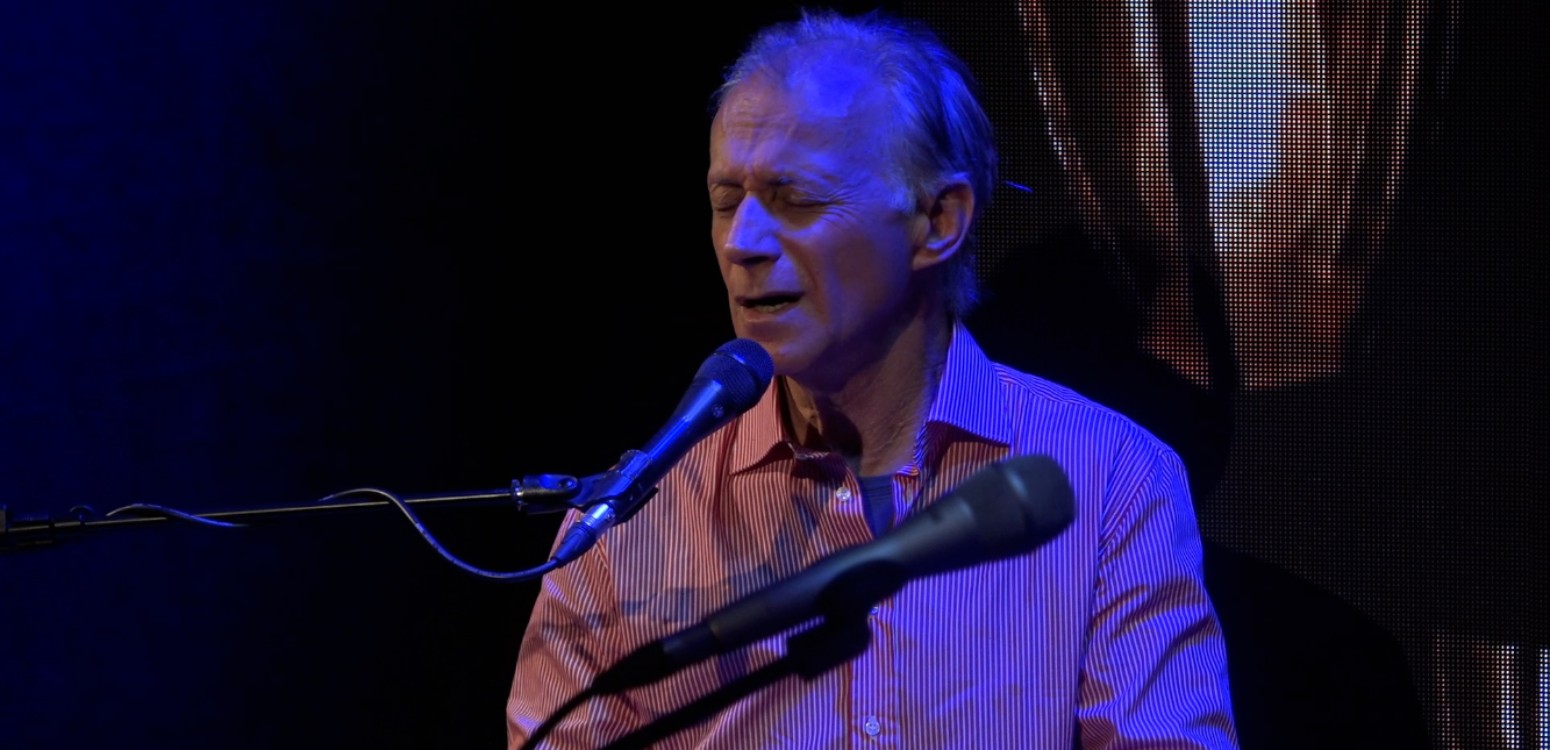

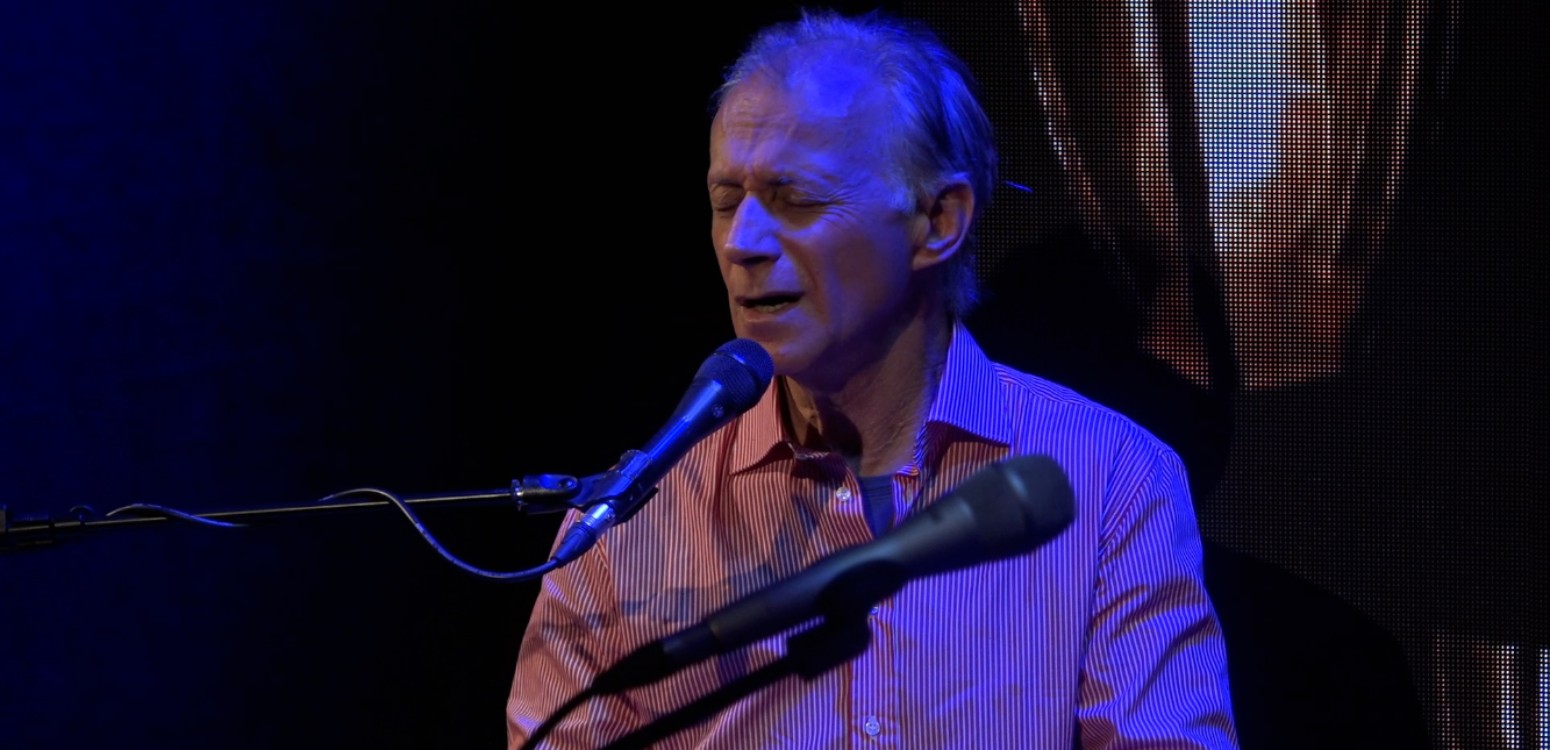

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Eikev, listen to “Source of Inspiration

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo:Created using AI

Also at Beit Avi Chai