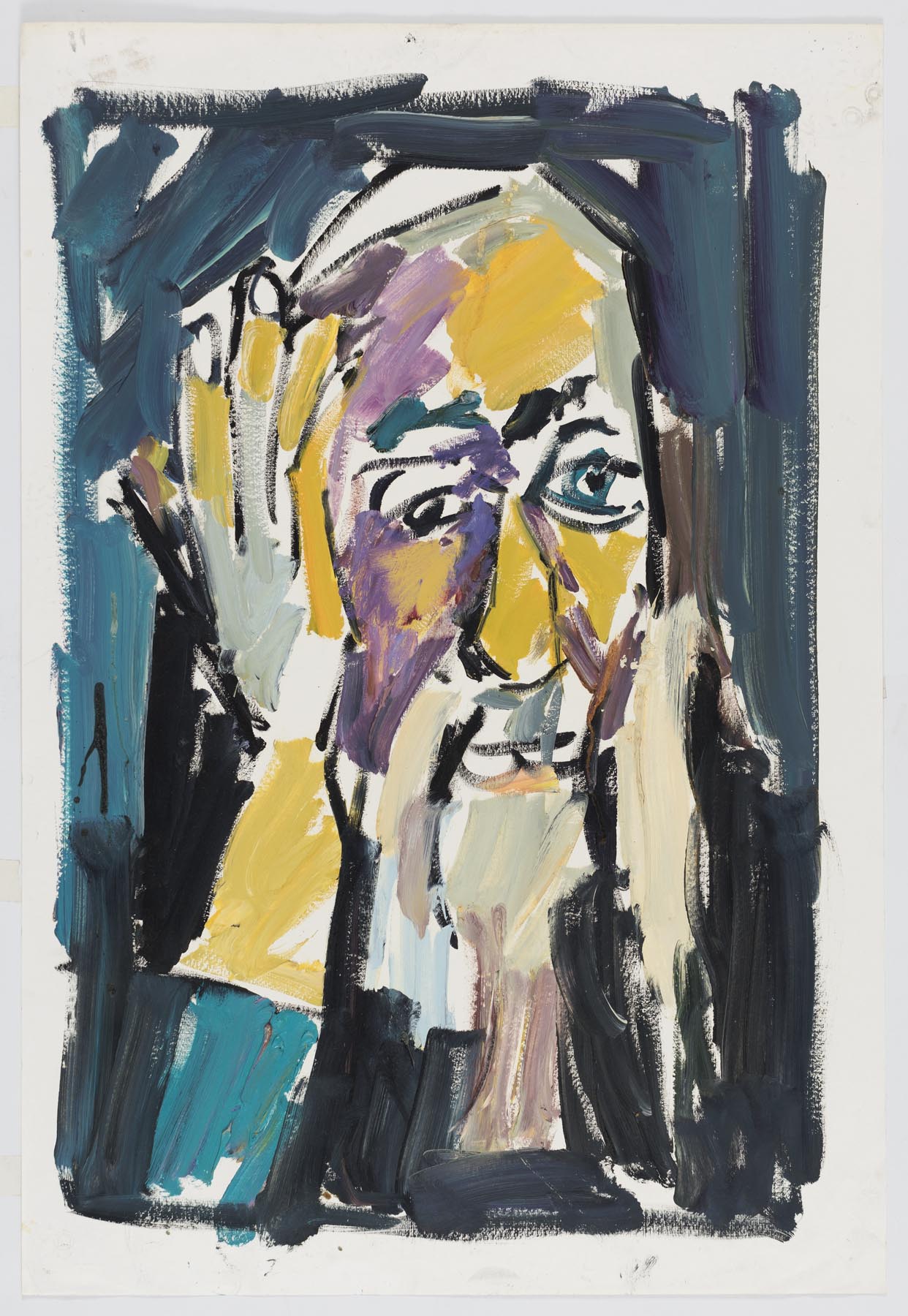

Among other subjects, Pinchas Litvinovsky painted many rabbinical portraits, but they were nothing like the sacred portraits we know from Christianity

Much of how we understand Pinchas Litvinovsky’s art is owing to speculation. Famously a recluse, he refrained from giving interviews or collaborating with other artists. What we are left with is his large body of work, serving as an almost unique witness to the themes that preoccupied him.

Such is his voluminous series of rabbinical portraits that, alongside his equally rich series of portraits of David Ben-Gurion, exhibit Litvinovsky’s ambivalent take on figures of power. The mere choice of using rabbis as the subject is a radical one: Due to the prohibition on visual representation of deity in Judaism, Litvinovsky did not have a rich tradition to tap into. Rabbinical portraits did exist, dating back as far as the early modern period, but their nature was nothing close to the centrality of Christian portraits, and the extravagant adulation that characterized them.

A marginalized tradition

“It wasn’t at all like Velasquez’ portrait of the Pope, Litvinovsky came from a very different place,” says Porat Salomon, a Jerusalem-based artist and curator, who earlier this month delivered a lecture at Beit Avi Chai on Litvinovsky’s series of rabbi portraits. “He uses them not as a motif but as raw material. He doesn’t paint the rabbis, he paints with the rabbis.”

Rabbinical portraits first appeared in Italy in the XVII century, mainly on covers of religious books that carried the author’s portrait. But from an early stage that tradition was marginalized and frowned upon, as a reaction to the centrality of sacred portraits in Christianity.

Like using postcards for landscape painting

“Basically what Litvinovsky is doing is reassessing the Jewish treatment of spiritual leaders,” Salomon says. “The rabbinical portraits are for him a springboard for religious reflections.” None of the rabbis modeled for Litvinovksy – certainly not the dead ones, but neither did his contemporaries. “He collected existing portraits and riffed on them,” Salomon says. “It was like using postcards for landscape painting.”

What Litvinovsky applied to these paintings, says Salomon, is not a creative maneuver, but a mere act of observation. “He was using his brush for the purpose of staring. Staring is observation, but with a purpose different from construction. It’s deconstruction, it’s blurring. He was using the material to make a philosophical claim, to penetrate the spiritual realm.” The fact that there are dozens of portraits from all denominations, he emphasizes, means that Litvinovsky was not interested in the rabbis and their thought, but in what they stood for. “They are cultural samples,” he says.

Turning a modern gaze to the past

The rabbinical portraits pinpoint Litvinovsky in a specific time and space. Born in the Russian Empire at the very end of the XIX century, he made aliya in 1919 and until his death in 1985 was a bulwark of Israeli art. The latter, by and large, sought to break away from the diasporic tradition and reinvent Jewish art. With the rabbinical portraits, Litvinovsky was looking back, not forward, but in a unique way.

In this sense he was different from Marc Chagall and his famous portrait of the Rabbi of Vitebsk. While Chagall looks back on the old world as lost and bygone, Litvinovsky attempts to revive the old world in a way that can be experienced in the new reality. “He is the new Jew, but one seeking to reconnect with the tradition of his ancestors,” Salomon says. “For him, the rabbinical portraits are not a symbol of the establishment, but an old family album. He wants to relive the foregone experience in a very tangible way.”

Still, Salomon insists, “he is a thoroughly modern painter, but one who wants to turn his modern gaze, somewhat nostalgically, to the past.”

Visit the Exhibition “You Must Choose Life – That Is Art: Pinchas Litvinovsky”.

Main Photo: Rabbi Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky (“The Steipler”; 1899-1985)\Pinchas Litvinovsky