When violence strikes, we blame individuals. But what if society bears responsibility? Through ancient biblical wisdom and a shocking Temple murder, we explore our collective accountability for bloodshed – forcing the question: Can we honestly say “our hands are clean”?

When violence erupts in our communities, we instinctively seek someone to blame. We want clear answers: Who pulled the trigger? Who wielded the knife? But what happens when we’re forced to confront the uncomfortable truth that we – as leaders, as citizens, as a society – might bear responsibility for creating the conditions that made such violence possible?

Imagine this scenario: A body is discovered by a riverbank, the victim of an unsolved homicide. In response, the nation’s highest officials announce an extraordinary public ceremony. At the victim’s gravesite, these leaders wash their hands before the assembled crowd and declare, “Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done.” They acknowledge that on their watch, this murder occurred, and pledge to examine what systemic failures might have led to this tragedy.

Atonement for an unsolved murder

This scenario isn’t fiction – it’s biblical law. The Torah prescribes exactly such a ritual in Deuteronomy 21, known as the ceremony of the beheaded heifer. When a murder victim is discovered and the killer remains unknown, community elders and priests perform a striking ritual by a stream, breaking a heifer’s neck and then declaring: “‘Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done. Absolve, o Lord, Your people Israel whom You redeemed, and do not let guilt for the blood of the innocent remain among Your people Israel.’ And they will be absolved of bloodguilt. Thus you will remove from your midst guilt for the blood of the innocent, for you will be doing what is right in the sight of the Lord.” (Deuteronomy 21:6-9)

But this ritual isn’t really about claiming innocence. It’s about confronting an uncomfortable truth: murder rarely happens in a vacuum. Violence often reflects deeper societal failures – broken systems, cultural norms that devalue life, inadequate education, or failed leadership.

The Torah refuses to let us dismiss each killing as an isolated act of individual madness. Instead, it demands we examine our collective role and ask the hard question: Did we fail to prevent what happened?

A competition turned deadly

This principle extends beyond unsolved murders. The Talmud tells a shocking story that illustrates how even when we know exactly who the killer is, society still bears responsibility. In the Temple, priests competed fiercely for the honor of offering the daily sacrifice – literally racing up the altar’s ramp to reach the finish line first. “Whoever reached the four cubits before his colleague shall merit,” the rule stated. What began as healthy competition turned deadly.

“An incident occurred where there were two priests who were equal as they were running and ascending the ramp. One of them reached the four cubits before his colleague, who then, out of anger, took a knife and stabbed him in the heart. Rabbi Tzadok then stood up on the steps of the Entrance Hall of the Sanctuary and said: Hear this, my brothers of the house of Israel. The verse states: ‘If one be found slain in the land... then your Elders and your judges shall come forth.’ But what of us, in our situation? Upon whom is the obligation to bring the heifer whose neck is broken? Does the obligation fall on the city, Jerusalem, so that its Sages must bring the calf, or does the obligation fall upon the Temple courtyards, so that the priests must bring it? At that point the entire assembly of people burst into tears.” (Yoma 23a)

A systemic failure

Rabbi Tzadok knew perfectly well that the beheaded heifer ritual applied only when the murderer’s identity was unknown – not in cases of public murder where everyone witnessed the crime. But that was precisely his point. He was forcing the community to confront their collective responsibility for creating a culture where sacred competition could turn murderous.

The writer and educator Arie Bodenheimer (1944-2017) explained that when violence erupts in places that should embody the sacred, it reveals a complete breakdown of the moral and ethical code – a systemic failure that cannot be atoned for through ritual alone, only through fundamental change.

The story’s most chilling detail comes at the end. As the stabbed priest lay dying, his father arrived and declared that the ritual knife used to murder his son remained pure because the

victim hadn’t yet died. The Talmud observes bitterly: “To teach you that the ritual purity of utensils was of more concern to them than the shedding of blood” (Yoma, ibid). Religious ideology had completely eclipsed human life.

Did our hands not shed this blood?

This is why the Torah places the beheaded heifer ritual precisely where it seems not to belong – in the middle of listing the laws of warfare. It’s not an editorial accident. When death rules and passions burn, when violence feels justified and blood runs cheap, the Torah forces us to stop and remember: every life matters. Every death demands accountability. And we – leaders and citizens alike – must be able to say with complete honesty: “Our hands did not shed this blood.” If we cannot, then the real work begins.

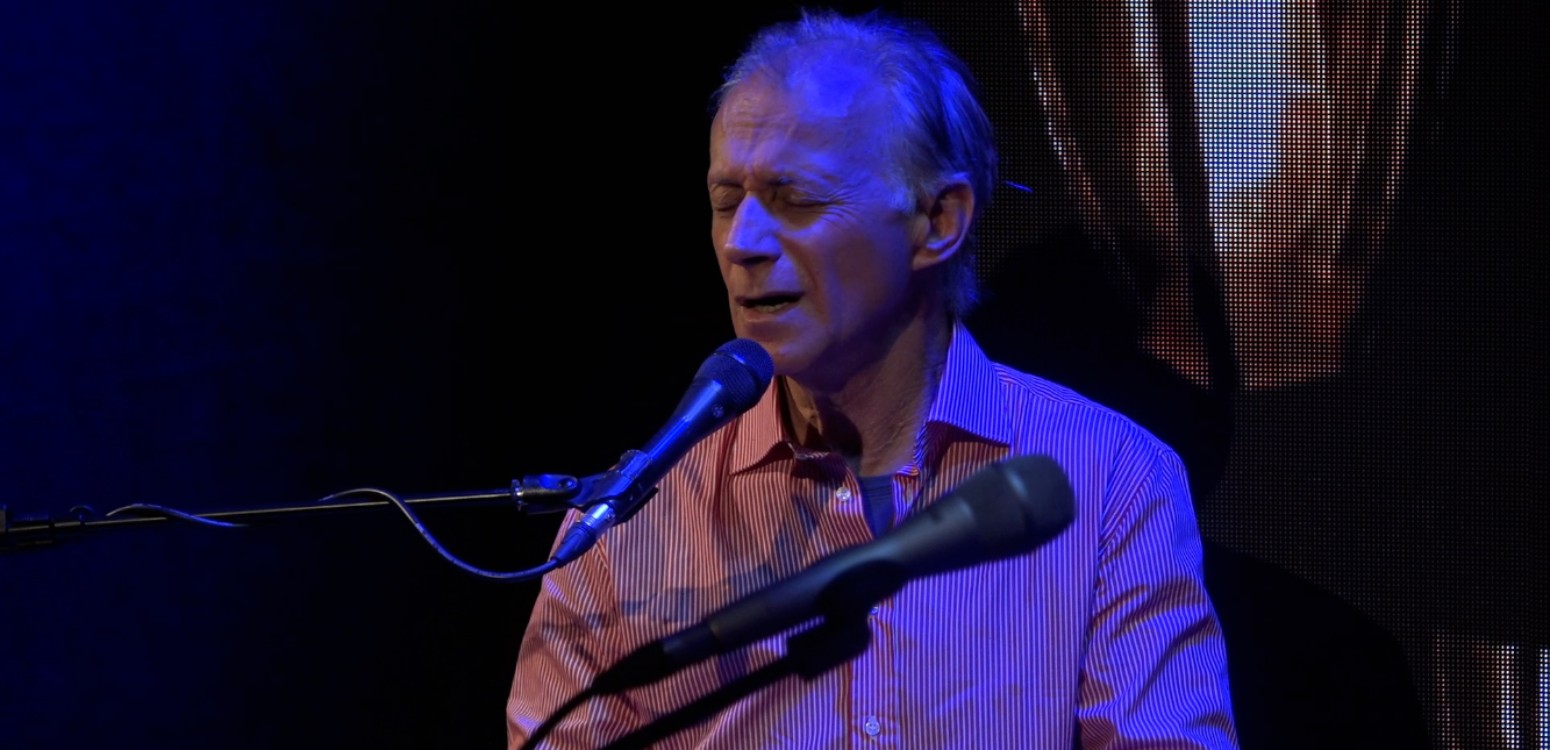

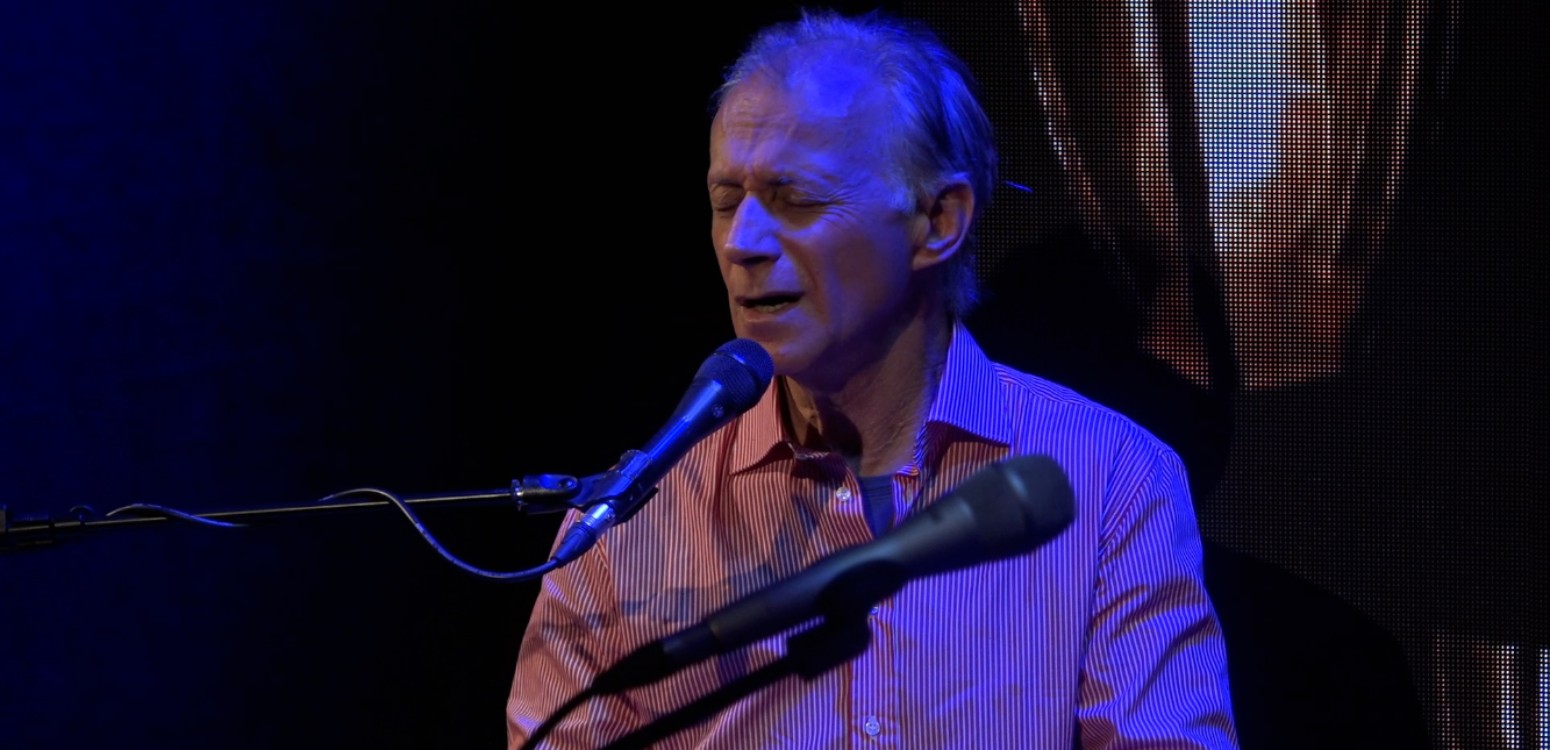

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Shoftim, listen to “Source of Inspiration”.

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo: Model of the Solomon's Temple, showing the the Council of the Sanhedrin\ Wikipedia

Also at Beit Avi Chai