Medieval demon-summoning ritual objects became today’s New Age trinkets: Dr. Gal Sofer reveals how Solomon’s magical seals transformed across two millennia of religious and cultural boundaries

In countless New Age shops around the world, tucked between crystals and tarot cards, you’ll find small medallions and pendants with intricate geometric designs, celestial symbols, and mysterious inscriptions. These are the “Seals of Solomon” – magical talismans promising everything from wealth and love to protection and healing. Few customers, though, realize they’re purchasing the modern incarnations of a magical tradition going back more than two millennia, crossing religious boundaries and reshaping itself through the hands of medieval monks, Renaissance physicians, and Kabbalistic rabbis.

Dr. Gal Sofer, a physician and scholar with a PhD in Jewish Thought, has spent years studying Solomon’s Seals. His four-part English lecture series at Beit Avi Chai, “The Magical Seals of Solomon,” promises to take audiences on an extraordinary voyage from the legendary origins of King Solomon’s ring to its special place in New Age culture.

“Solomon himself was a cosmopolitan figure venerated by all – Jews, Christians, Muslims,” Sofer explains. “That’s why this kind of amulet became a shared passion. People of different religions could meet and exchange ideas, developing these amulets together.”

Commanding angels and demons

The story begins around the first century, when people first spoke of Solomon’s seal – a magical instrument with which the king controlled demons to build the Temple in Jerusalem. Josephus wrote that someone called Eleazar used a ring like this in the presence of the Roman Emperor Vespasian. According to early legends, the seal bore inscribed divine names that granted Solomon dominion over the spiritual realm, allowing him to command angels and demons alike.

“The earliest known reference describes Solomon’s seal as something preserved in different kinds of materials,” Sofer says. “But at some point in the Middle Ages, it became something you could design and reshape – an idea rather than a specific instrument or seal.”

This transformation from a singular legendary artifact to a flexible magical concept proved crucial to the seals’ enduring appeal. “Someone thought that all this knowledge should be organized,” Sofer explains. “Then you find catalogues of Solomon’s seals – a big data revolution. There were so many different kinds of amulets that practitioners needed to sit down and try them all. Now there are many different kinds of seals of Solomon that you can buy in New Age shops, each one promising different benefits – wealth, healing, love, even causing someone to die or healing them. The tradition is still developing.”

The pentacles as canvasses for contemporary knowledge

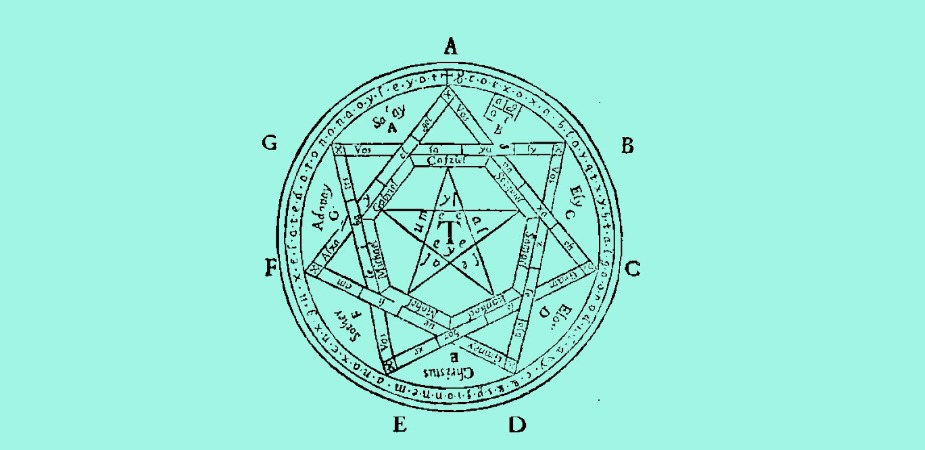

Sofer likes to focus on a pivotal transformation in European magical traditions: the birth of the pentaculum as the new seal of Solomon. This represented a fundamental shift in how these magical instruments were understood and used. “The visual designs changed as new kinds of knowledge were developed,” Sofer explains. “In late antiquity, you might find the figure of Solomon killing a demon engraved on a gem. But when astrological elements entered learned magic, and when alchemical knowledge was incorporated, they became part of the seals of Solomon as well.”

The pentacles became canvasses for contemporary knowledge. In the early modern period, they featured symbols and angelic names reflecting current astrological understanding. “The amulets are a mirror of existing knowledge,” Sofer observes. “If you want love, you’ll use Venus symbols with angelic figures.”

Magical traditions adapt to survive

This evolution reveals something profound about how magical traditions adapt and survive. Rather than remaining static relics of the past, the seals of Solomon continuously absorbed new intellectual currents, from astrology and alchemy to medicine and natural philosophy.

Perhaps most surprising to modern audiences is the originally demonic nature of these instruments. Sofer’s research reveals that the seals of Solomon we see today have their roots in medieval demon-summoning rituals. “I believe that the most common seals of Solomon we find today are rooted in demonic ritual,” he explains. “You first find them in rituals for controlling demons – practitioners standing in the center of an incantation circle in robes and with wands in their hands. When a demon appeared, the practitioner showed the amulets to establish their authority.”

From demonic rituals to modern pragmatism

This demonic context has been largely stripped away from modern versions. “The amulets being used today have been removed from this demonic context because people want to use them in a more pragmatic way. But it all started with demonic rituals.”

This transformation reflects broader changes in how Western culture approaches the supernatural. Where medieval practitioners sought to command spiritual beings through elaborate rituals, modern users typically want practical benefits without the theological complications.

Sofer’s unique background as both physician and scholar of Jewish thought led him to discover fascinating connections between medical and magical practices. “Being a physician led me to discover how medical practitioners took this magical device and turned it into a medical instrument, even inside universities.”

“In medieval and early modern Europe, the boundaries between magic and medicine were far more porous than today. Many seals were already being used in medieval universities, where physicians employed astrological seals, but some people thought they were demonic in nature. Some rejected them for being demonic, others dismissed them as superstitious, while still others used them,” says Sofer.

Cultural appropriation and transformation

Perhaps the most complex chapter in this story is how Jewish scholars in the XVIII century encountered and transformed Christian Solomonic traditions. Sofer’s research focuses on a Hebrew text called Sefer ha-‘Otot (“The Book of Signs”), which represents a fascinating case of cultural appropriation and transformation.

“Jews knew that some of this knowledge was of Christian origin, but viewed it as stolen knowledge that needed reclaiming,” Sofer explains. “A Dutch rabbi said he extracted the knowledge ‘from between the legs of the pig’ – a rather colorful way of describing how he purified Christian magical texts for Jewish use.”

This involved sophisticated theological and halachic considerations. “When they presented these amulets, they needed to ask whether they could use them or not, and if so, how. There were extensive debates surrounding this issue.”

The Sefer ha-‘Otot was written by two XVIII-century rabbis, including Yehuda Peretz, a Sabbatean involved in various scandalous events who was also probably a forger of books. Sofer discovered the manuscript nearly 11 years ago, and it took him three years just to identify its anonymous authors.

“Peretz preached at the Ashkenazi synagogue in Venice for some time, even though he was of Moroccan descent. He was born in Ragusa [present-day Dubrovnik], and then traveled throughout Europe working on the book with his students. He wasn’t bothered by the halachic aspects, but his partner Isaac was, and some of the recipes were censored.”

An ever-evolving idea

The journey from medieval grimoires represents yet another transformation. “Manuscripts were translated into English in the XIX century by magicians and printed, becoming bestsellers that remain popular today. Much later, in the last 20 years, people began seeing the amulets as objects they could use outside their original ritual context. That’s why you find Solomonic amulets across New Age shops today – there are even mugs and t-shirts.”

Sofer views this as both a departure from and a return to earlier traditions. “Before they were demonic instruments, they were probably used as protective amulets, so in some ways this represents a return to their original usage.”

Despite these developments – or perhaps because of them – Sofer encounters frequent misconceptions about Solomon’s seals in popular culture. “People think there’s a very specific shape or form. They say that the pentagon or hexagram or Magen David is the seal of Solomon – they speak about it as a shape when in reality it’s an idea that has been circulating for thousands of years and reshaping itself according to people’s needs. The idea is always evolving.”

This flexibility has been key to the tradition’s survival across different historical periods and cultural contexts. From ancient Jewish legends to medieval Christian grimoires, from Renaissance medical texts to New Age stores, the seals of Solomon have proven remarkably adaptable. Today, they continue on their journey, adapting once again to contemporary needs while carrying the fascinating legacy of their extraordinary past.