When debt feels like venom, the Torah offers a cure: lending without profit, rooted in love and mutual responsibility. A timeless vision of brotherhood in an age of business

Hidden within Parashat Ki Teitzei, alongside laws about lost property and worker’s rights, lies one of the Torah’s most radical economic commandments: the absolute prohibition against charging interest from fellow Israelites.

“You shall not deduct interest from loans to your fellow Israelites, whether in money or food or anything else that can be deducted as interest; but you may deduct interest from loans to foreigners. Do not deduct interest from loans to your fellow Israelites, so that Lord your God may bless you in all your undertakings in the land that you are about to enter and possess.” (Deuteronomy 23:20-21)

A life of perpetual fear and misery

Interest is called neshekh. Some commentators explain that this word is derived from the word neshikha, “bite”. Rashi writes on a parallel verse in the book of Exodus: “‘Interest’ because it is like the bite of a snake which bites [inflicting] a small wound in his foot which he does not feel and, suddenly, it burgeons and swells [his entire body] till his head. So it is with interest: He (the borrower) feels nothing and it is not noticeable [at first] until the interest accumulates and causes him a great loss of money.” (Rashi on Exodus 22:24)

The snakebite metaphor proves devastatingly accurate. Financial distress forces someone to borrow, but they can’t repay the growing debt. So they borrow again, and again, until interest plunges their life into perpetual fear and misery.

The Torah envisions something radically different: lending as an act of brotherhood, not business. Those blessed with means should help others without profiting from their desperation. The common justification – that interest merely compensates lenders for lost opportunities – doesn’t apply. If helping your neighbor costs you something, absorb the loss. That’s what mutual responsibility demands.

Mutual responsibility

In practice, the prohibition on interest expresses a special consensus within a society that seeks to build itself on the foundation of mutual responsibility. From the perspective of simple law, a person could seemingly do with their money whatever they want, as long as it’s done with transparency and the consent of all parties, but mutual responsibility teaches otherwise. Ramban explained it as follows:

“And he explained here that a heathen’s interest is permissible. This he did not mention with reference to robbery and theft, as the Rabbis have said. ‘Theft from a heathen is forbidden.’ But borrowing for interest, which is agreed upon by both parties and is done voluntarily, was forbidden [by the Torah] only because of brotherliness and kindness, as He commanded, ‘and thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself,’ [...] for it is an act of mercy and compassion that one does for his brother by lending him without interest, and it will be accounted to him for righteousness.” (Ramban in his commentary on Deuteronomy 23:20)

Building a society on charity and kindness

Those who believe society must be built on charity, kindness, and love – not just on contracts – can understand why the Torah forbids interest. And indeed, most major religions tried to uphold the same value: Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism all contain prohibitions against interest. Yet in practice, people everywhere found ways to get around the ban.

In Judaism, the best-known workaround is the heter iska (“business permit”). It draws a line between two kinds of loans: business investments, where interest is allowed, and personal loans to the needy, where it is not. But this distinction was quickly neglected. Almost every loan came to be labeled a “business deal,” and interest seeped into daily life. Banks turned it into a system: charging everyone, encouraging constant borrowing, and ensnaring people in endless debt.

Exploitation masked as agreement

The Torah calls on us to resist the snakebite – exploitation masked as agreement – even when contracts make it seem acceptable. It asks us to imagine a society where brotherhood outweighs profit, and where responsibility for one another is the true currency. That vision is still within reach, if we choose to live by it.

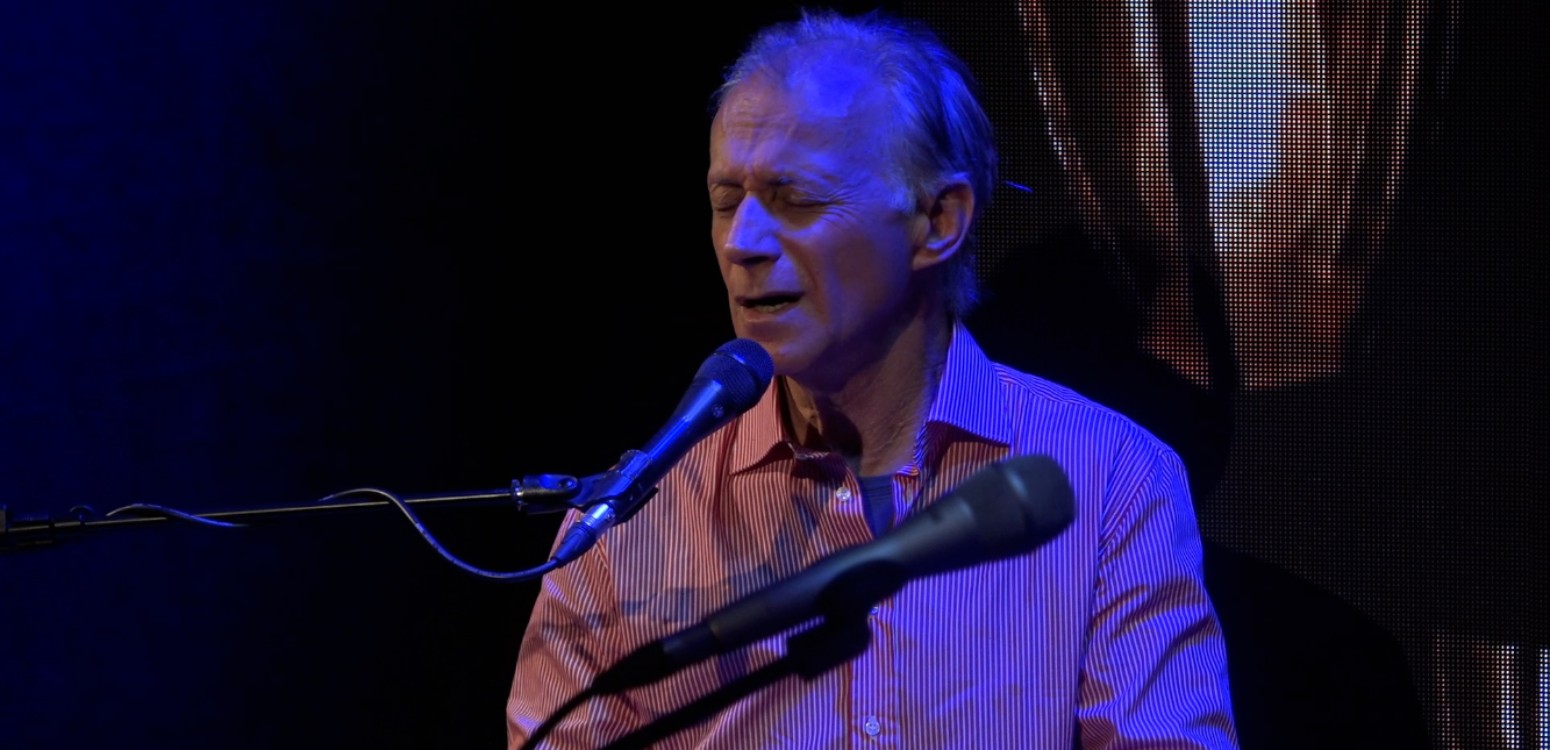

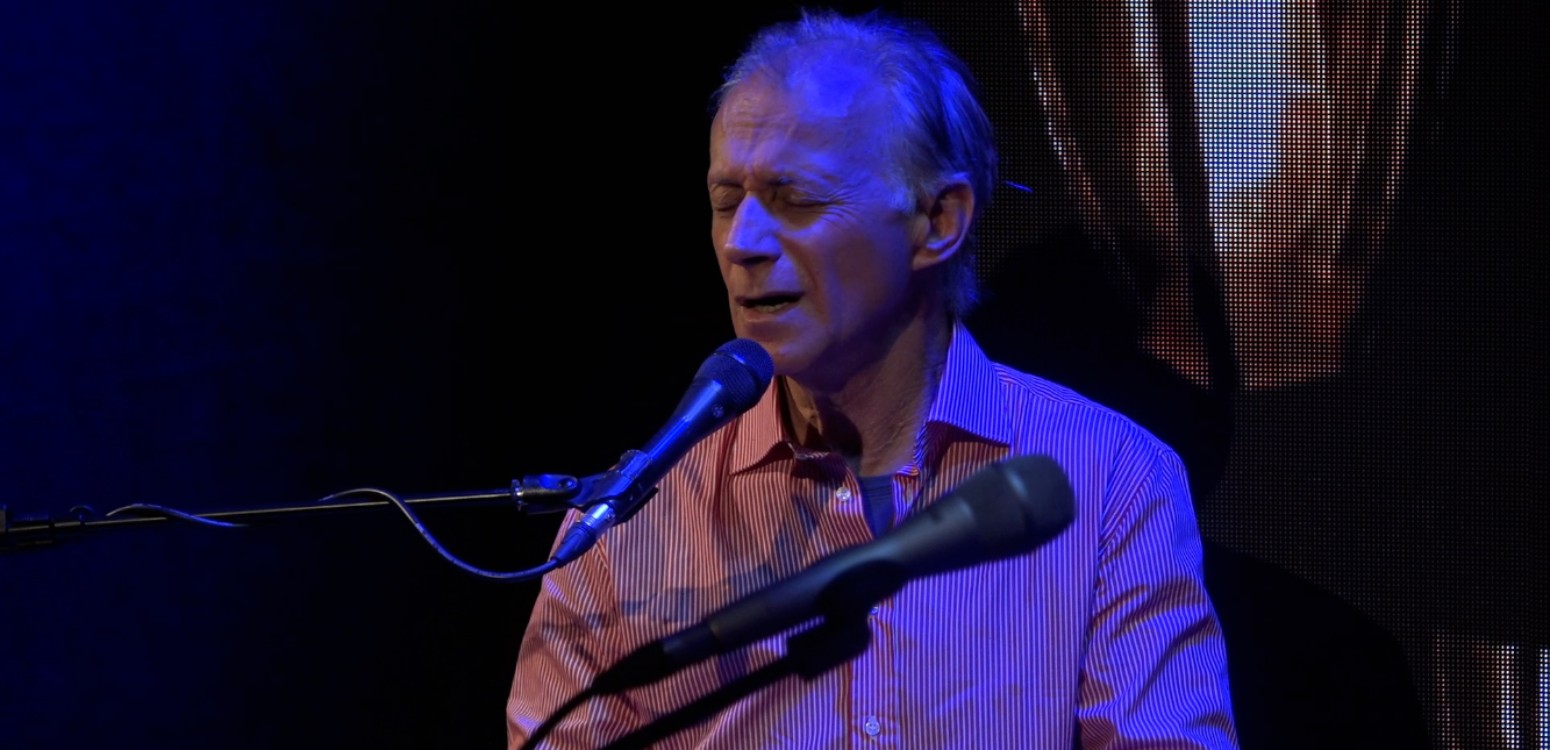

Lior Tal Sadeh is an educator, writer, and author of “What Is Above, What Is Below” (Carmel, 2022). He hosts the daily “Source of Inspiration” podcast, produced by Beit Avi Chai.

For more insights into Parashat Ki Teitzei, listen to “Source of Inspiration”.

Translation of most Hebrew texts sourced from Sefaria.org

Main Photo:Created using ChatGPT

Also at Beit Avi Chai