A conversation with artist Noga Greenberg about paralysis, returning to creation, and the role of art in wartime

“Times when I’m not creating bring with them depression, a feeling of something being wasted, like there is such an abundance before me and I’m doing nothing with it,” says Noga Greenberg (born 1985), one of the artists participating in Beit Avi Chai’s group exhibition, “My Life at the Moment.”

Greenberg’s series of analog photographs presents intimate and tender scenes within a complex and difficult period. Greenberg documented routine life on the home front which existed between runs to protected spaces. The photographs, mainly capture the family setting, show everyday moments in the shadow of war: a siren, laundry, “cleared for publication,” dinner, crying, sleep.

While the cannons roar, girls continue to celebrate birthdays; white shirts hang to dry in the sun like a civilian white flag; the flowing light continues to illuminate; and a superhero figure lying casually on the dashboard reminds of the childlike hope for a Hollywood solution where good must triumph. The human figures in Greenberg’s photographs are cut off, partial, almost incidental. The landscape captured by her lens responds to the same syntax: nature is beautiful but not quiet.

When the war burst into your studio, were you in the middle of working on something else?

“When the war broke out, I was between two solo exhibitions with a clear line drawn between them, and it was cut off immediately. The exhibition I was about to present appeared to be a direct continuation of a process that began, quite symbolically, right after the exhibition I showed at the gallery in Kibbutz Be’eri, in November 2021.

“I had started to explore what happens at the edge of the film roll, the place between the ‘living’ and ‘dead,’ between the image and the edge of the material that was immersed in chemicals, and I was excited by the surprising visual phenomena that form there. With the intention of corresponding with feminist art and with midrashim about the distance between the upper waters and lower waters, I put film rolls in the washing machine and dishwasher, but after October 7, nothing could continue as it was. I completely disconnected from the act of creation for several months. When such a fundamental truth slips out from under our feet, I didn’t feel there was justification for art in the world. There’s something quite privileged about creating art. It’s not for nothing that Abraham Maslow didn’t place creativity in the more basic levels in his ‘hierarchy of needs.’ Art needs certain conditions to exist, and I felt that the basic conditions were no longer there. Time passed, the pain of reacting to reality dulled, and art returned to my life.”

So, at first war created creative paralysis for you.

“Yes, I went through many months of paralysis. Even writing to myself was difficult. But there was a deadline for an exhibition in Tel Aviv, in March 2024, and the moment arrived that I couldn’t escape from. I reached the decision that I wasn’t giving up on this exhibition, but I was approaching it from a different perspective. Lack of control has always been a theme in my work; I’ve always appreciated the fingerprint of chance, but once I returned to creating, I felt that my control was slipping away completely and that I was setting out on a new path, a breaking of vessels. I could no longer tolerate my own mannerisms, those same abstract places to which I’m always drawn. If I’m fated to create, I must discover a new field, to emerge from a different place in the brain.

“I defined this exhibition as an absolute experiment. I gave up any aspiration for a finished creation that would appear there. I allowed myself to meet anew with the materials and with reality from a more humble place that accepts imperfection as an accomplished fact. In a circular way, I naturally returned to the same subjects that preoccupied me before – this time from a different perspective, colored in the shades of the period.

In the last two years, my work has been more documentary; it’s based on raw materials from concrete reality – and the works in the exhibition represent this dimension in my creation.

Do you think art is better when it’s created after a while – after gaining some perspective on the events that occurred – or when it’s created in real time? There are criticisms raised about post-war art, claiming one should wait a while and process, so that things have artistic value. What’s your opinion on this?

“Every work of art contains elements of time and place. I’m not talking about the simple documentary aspect, of course. Even Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” (1915) sheds light on the time and place in which the work was created. There’s an element in art that’s connected to artistic language, to the spirit of the times, to the here and now, but that’s not enough. In good work there’s also a dimension of universality and aspiration to infinity. Work that refers only to contemporary issues without touching on the existence of the sublime and infinite will remain a curiosity as time passes. The artist must try to keep one finger on the here and now and one finger on eternity. The foundation of infinity touches on profound questions that humanity has carried since the dawn of its existence. But this, in my view, is the division between a work that has existence in the perspective of time and a work that has an expiration date.

Art that recognizes both the temporal and the eternal will be good and interesting both immediately and in the long run.”

Do you think that we are facing a depressing era in museums and galleries? Are we facing a decade of sad and dark post-war art?

“I hope not. Unambiguous or monochromatic art is worthless. I return to the question on time perspective: an artist must be connected to what’s beyond the here and now. Pain and bereavement will appear, but they’re not the whole picture. The artist must respond to events, but from a broad perception of reality. Painful Jewish history existed as a subject before October 7, and it receives new validity every morning, unfortunately. It’s possible that Jewish identity and Jewish fate will receive more spotlight in Israeli creation in the coming years, similar to what’s happening in public discourse.

Judging from this point in time, I think that Israeli art – similar to the process I went through myself – has returned to themes that were on the agenda even before the war, and bereavement and pain are among them.”

What in your view is the role of art? For whom and for what are you doing this?

“I make art, first of all, because I can’t not make art. It’s not a choice; it’s a compulsion. There’s that moment in every work, the moment of discovery: something new has been created here; a small spark has descended to earth; a feeling that things are in their place, that I’ve managed to say something.

The act of art seeks to add something into a lacking world. The work of art is born from the place of discomfort, from a deep point of friction between me and the world. When people ask me why art and melancholy are such good friends, I first of all agree with the basic premise: art is created where there’s a void. Our souls are founded on the desire for repair (tikkun). It might sound too dramatic to say I create to repair the world. That’s obviously not what I tell myself when I’m working on a project, but deep down, it’s the undercurrent that drives everything.

“Why do we need art? The individual needs art because it expands the emotional and intellectual range. It raises questions and it can bring tears up from deep places. Society needs art to establish identity, cultural belonging, a common language, collective existence on the higher plane.”

Visit the exhibition “My Life at the Moment”>>

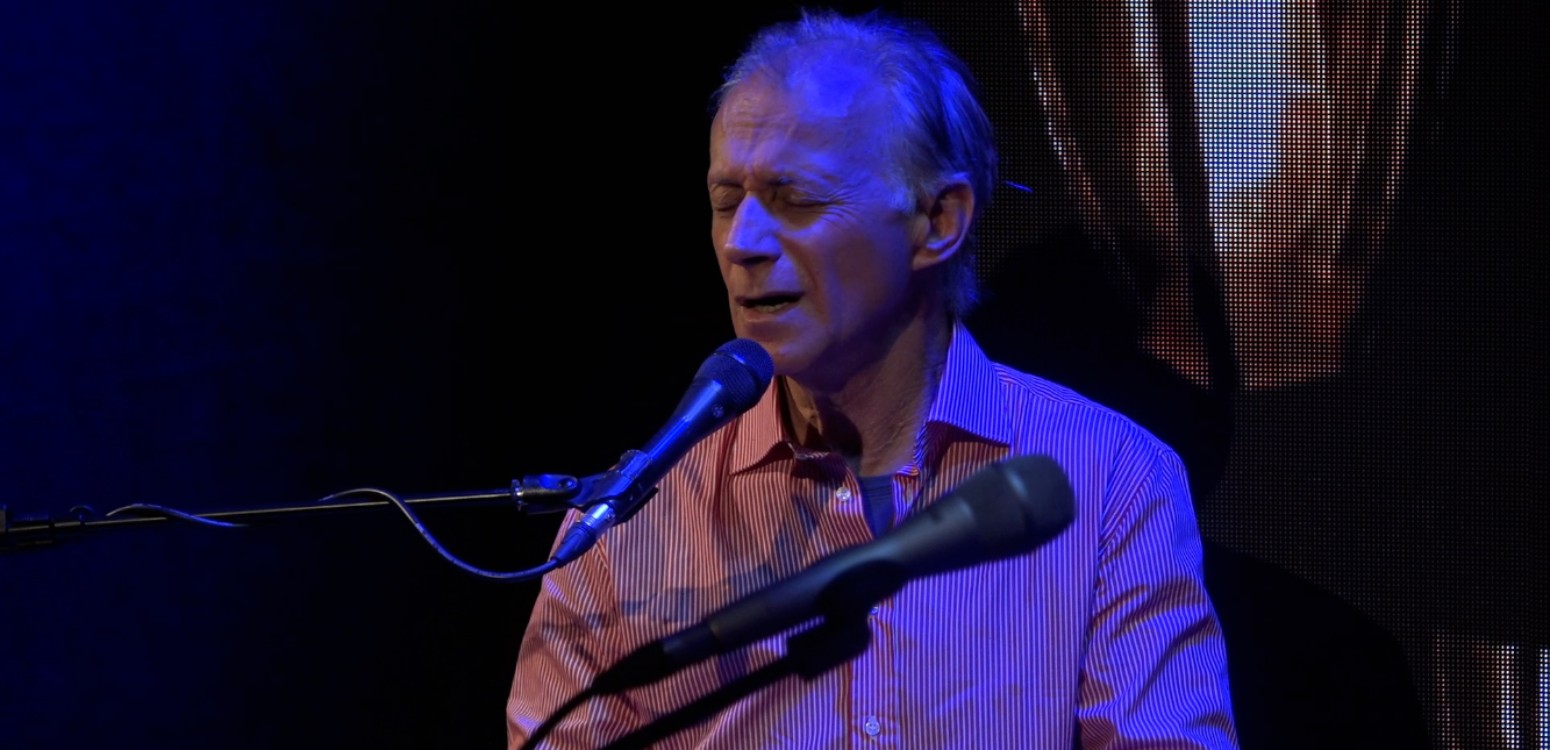

Main Photo: Twenty-Four Windows, 85x80 cm. 35mm photography.\ Noga Greenberg

Also at Beit Avi Chai